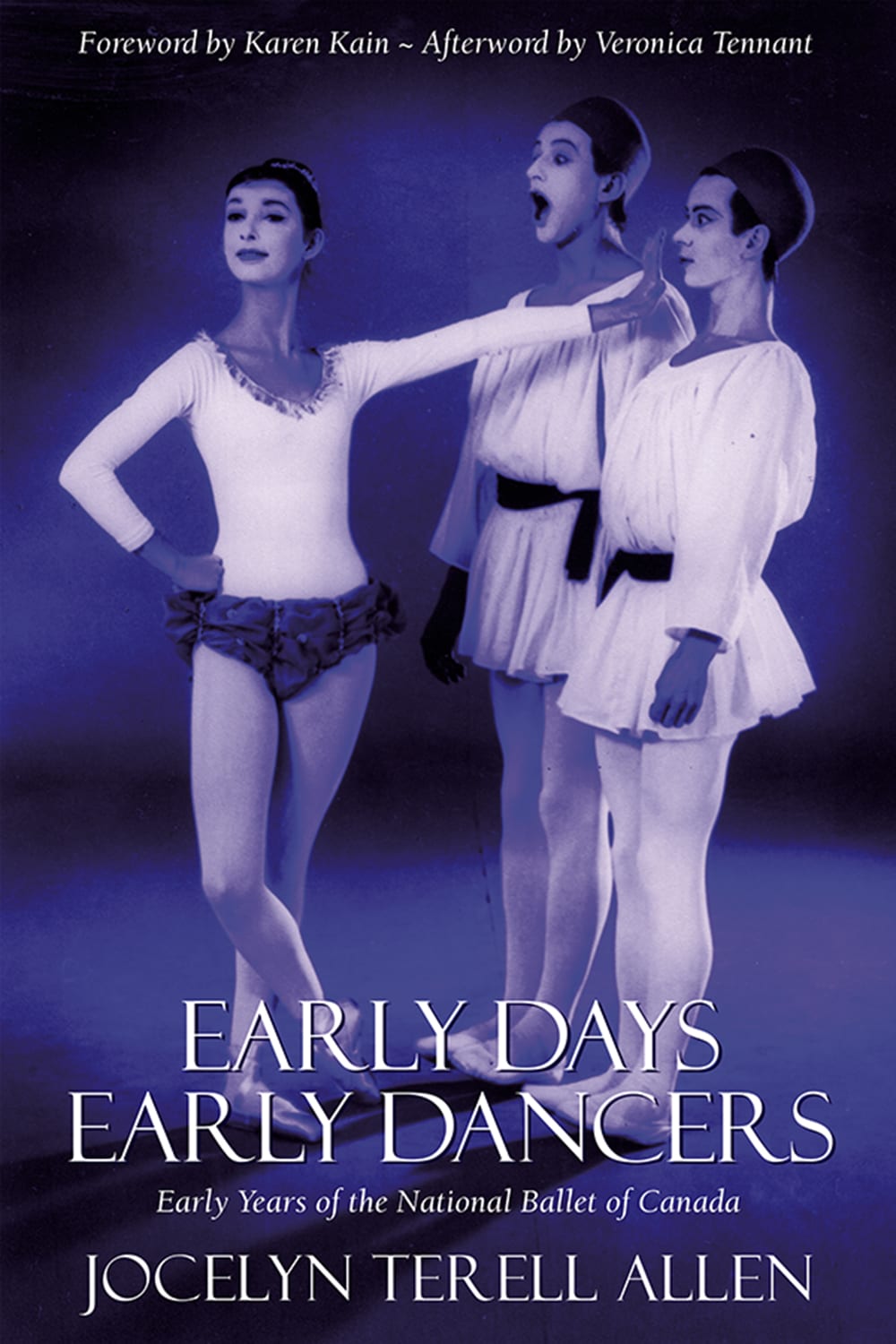

Early Days, Early Dancers documents the first decade of the National Ballet, focusing on the dancers of the 1950s, especially principal dancers Lois Smith, David Adams, Angela Leigh, Donald Mahler, and Celia Franca, herself a dancer and later the Company’s Artistic Director. With an enthusiastic foreword by Karen Kain, and a moving afterword by Veronica Tennant, the book includes pieces by twenty-two dancers, plus memorial tributes to dancers who have passed away. Contributions explore the dancer’s journey through St. Lawrence Hall, summer school, rehearsal, and life on tour, as well as life after a career in dance. Portraits includes comments by the dancers on such figures as Celia Franca, Betty Oliphant, and Kay Ambrose among others, and memorial tributes to those dance figures who have died are written by well-known writers contemporaries such as Michael Crabbe, John Fraser, Vanessa Harwood, and Veronica Tennant. These memories of the Company’s early dancers provide a unique impression of the origins of the National Ballet, and the history of dance in Canada, and highlight the way the present dances on the shoulders of those who have gone before.

Jocelyn Terell Allen became a dancer with the National Ballet Company in 1956 at the age of sixteen. She danced for the first time, as a member of the corps de ballet, in the Carter-Baron Amphitheatre in Washington, DC., studied dance in New York and London as a member of the Company, and became a principal dancer in the fall of 1963. She danced for half her life and then a series of injuries forced her to have to adjust to life without dance. She enrolled in York University as a “mature” student and subsequently completed a Master’s degree in English at the University of Toronto. In later years, she was privileged to sit on the boards of the Dancer Transition Resource Centre, or DTRC, and Peggy Baker Dance Projects. She married Peter Allen, had three sons and now has six grandchildren. She continues to enjoy attending ballet, theatre and the arts, and she loves to write.

Foreword

Those of us who have enjoyed long and satisfying careers through the most recent decades at the National Ballet of Canada owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the pioneers who came before us. It is wonderful to read of the trials, tribulations, and triumphs of those early years, and to imagine how different it must have been when the Company was first founded in the fifties.

The first-person accounts you are about to read conjure the sights, the smells, and the sweat that contributed to the National Ballet’s formative years. The tributes written to those who have left us exemplify the kindness and courage that formed the foundations of the National Ballet.

A huge thank you to all who contributed to bring this important part of our history to life, and a special thank you to Jocelyn Terell Allen for the Herculean effort she undertook to compile these stories in Early Days, Early Dancers. To those whose shoulders we all stand upon—many, many thanks.

—Karen Kain, C.C, L.L.D., D.Litt., O. Ont., Artistic Director, National Ballet of Canada, September 2019

Early Training

Imagine that you wanted to dance more than anything else in the world, and that Celia Franca, a dancer from the revered Sadler’s Wells Ballet of London has come from England to form a Canadian ballet company. This company could be your one chance to dance professionally in Canada. As artistic director, Franca has the final say about who will dance with her company. How was this small group of dancers able to take advantage of that chance, perhaps the only chance? There are two basic questions to consider here: Where did the motivation come from? Who and what enabled them to take advantage of this life-changing opportunity?

First, it is important to place these stories into an historical context. The year 1950, when Franca agreed to come to Canada and face this monumental task, was ten years after the end of the Depression of the 1930s, and only five years after the end of World War II. Partly because of these tragic conditions, Canada had opened its doors to hundreds of thousands of immigrants. They were fleeing war-torn Europe and bringing their energy and culture with them to late 1940s and early 1950s Canada. According to the Canada Year Book, over one million immigrants entered Canada between January 1946 and June 1954. The total population had gone from just over twelve million to just over fifteen million. This arrival of talent and culture and energy provided an opportunity for Canada to grow not only in population, but also in industry, economics, and the arts. Many of these early dancers and their teachers had a connection to the people, events, and cultures of Europe.

For some of the dancers, World War ii had a personal and horrific impact. Marcel Chojnacki was born in Brussels in 1932. When Hitler invaded Belgium in 1940, most of Marcel’s family, which included six children, were sent to the concentration camps and their deaths. He and two of his brothers spent the remaining war years in orphanages. When they came to Canada in 1947, they settled in Toronto with other Jewish orphans. In the spring of 1948, Marcel went to see a movie called The Red Shoes. This film is based on a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, in which a young ballerina joins a ballet company and becomes the lead dancer in a ballet called The Red Shoes. Marcel was enthralled by the role of the Shoemaker, performed by the Russian dancer, Leonide Massine, who choreographed his own part in the film. Marcel decided on the spot that he wanted to be able to create the kind of magic that Massine had created in the film. He stated, “I danced and leapt out of the movie theatre that day thinking, ‘That’s the life for me!’”

His first step was to find a studio and a teacher. Marcel started his training at the Young Men’s Hebrew Association in modern interpretive dance classes, which used the Martha Graham technique. He also joined the New Dance Theatre. Most importantly, Marcel discovered Boris Volkoff’s ballet company. “Boris Volkoff made it possible for me to come as often as I was able” for reduced fees. He then studied with Betty Oliphant, who was teaching along with Celia Franca. With this solid background, he was accepted into the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in London for training during the years 1954 and 1955. One of his teachers there was Harold Turner, a ballet master who had a Saturday morning class for men. Upon his return to Toronto, he joined the National Ballet.

The Laine Metz School of Ballet in Edmonton was based on the teaching methods established by Mary Wigman in Germany in the early part of the twentieth century. Laine Metz had performed with Mary Wigman, in Europe. Metz fled Estonia after the War and when she arrived in Edmonton, she opened the Laine Metz School of Ballet, bringing the rigorous Eastern European teaching methods to her Canadian students. One of her top students was Grant Strate, later a founding member of the National Ballet of Canada, and the company’s first resident choreographer.

Another Laine Metz student was Edelayne Brandt. Brandt hadn’t planned to become a dancer. “I simply danced my way into it,” she says. It was fortunate that her family moved to Edmonton; at ten years old she was enrolled in the Laine Metz School. Celia Franca was so impressed with her skills when she first saw Brandt perform in a small recital that she asked her parents if the young student could come to Toronto to study with Betty Oliphant. Brandt’s parents thought twelve was a bit too young to leave her family and move halfway across the country for ballet lessons. A year later, when she was thirteen, Franca made the request again, and this time Brandt’s parents agreed. Soon, she was on a train to Toronto accompanied by Laine Metz. Then, because she was so young, her parents decided, “generously and courageously,” that the entire family would move to Toronto with her. One of the first people Brandt met at the summer school was an equally young, naïve, and terrified dancer, Jocelyn Botterell, whose stage name later became Jocelyn Terell.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.