These poems dwell in the hearth of domesticity, but they look beyond the confines of the home with clear eyes. Boldly unafraid, they confront the realities of climate change, the desecration of habitat, some quiet truths about aging and death. There is no doubt that these are poems written by a woman. But even though many of them deal with the domestic world long considered the ‘domain’ of females, they reach well beyond the realm of the kitchen and tradition. They are a celebration of the quiet glory ensconced in the ‘practical’ nature of the everyday world, even though that world may often feel overwhelmingly filled with ‘anxiety.’

“Heidi Greco’s abundantly generous new collection, Practical Anxiety, sings “praises to the light.” Not afraid to hold death in her open hands, Greco is also alive to the “happy slurry of life.” This is poetry of breadth and depth, shimmering with firefly-quick intelligence and imagination. It is a book to cherish.”

—Anne Simpson, author of Loop

“Heidi Greco’s poems in Practical Anxiety capture the recollected fears of childhood in the bowl of “bedtime hands,” and acknowledge, to an almost-honouring of, the irky angsts being an adult is amid its “skeltered” piles of unwashed dishes. Greco rewrites the psalms, celebrates threatened “blood-ruddy” ecosystems, reminds us of the dangers in “clutching remotes instead of each other.” This collection of lyrical noticings can’t simply be summed up as “domestic,” but instead must be considered as a set of vital knowings from one fully alive woman’s life. A moving and necessary collection!”

—Catherine Owen, author of The Day of the the Dead and Dear Ghost

“This collection is a triumph. In her detailing of “anxieties” that give her “practical” poems, in her sounding of clear notes of bewilderment, celebration, reflection, intense observation of other people and the natural world, and many-levelled love, Greco signs up her life under a scrupulous, subtle lyricism, with warmth and with never-failing charm.”

—Russell Thornton, author of The Hundred Lives

“Practical Anxiety is a book of wonders and dreams, questions and calls to action, meditation, eulogy and prayer. sometimes with all of these elements acting at once.”

—subTerrain

Andrew Parkin –

Honouring everyday anxieties

Practical Anxiety by Heidi Greco

reviewed by Andrew Parkin

BC Booklook – February 13, 2019

https://bcbooklook.com/2019/02/13/485-honouring-everyday-anxieties/

Heidi Greco is known already from her previous books of poetry, notably those about Amelia Earhart, A: The Amelia Poems (Lipstick Press, 2009) and Flightpaths (Caitlin, 2017). I enjoyed her live reading from these books in New Westminster last year. Her latest book of poems, Practical Anxiety, is in six parts or sections; this suggests that Greco has read Auden’s Age of Anxiety(1947) that was organized into six “eclogues.” In fact, she quotes from Auden’s book as a sort of preface to her own: “The gods are wringing their great worn hands/ For their watchman is away, their world engine/ Creaking and cracking.”

Auden’s title is as striking as those lines recalling the enormous worry of the bare survival of civilization: survival after two world wars and the invention and use of the atomic bomb, linked to the new menace of the communist dictator Stalin’s possession of atomic secrets given to the Soviets by the ideologically motivated scientist spies. The constant anxiety during the “Cold War” has now faded, even with the old KGB man, Mr. Putin, in charge of Russia, territorially the largest country on earth; yet anxiety remains about the possible use of atomic weapons by the leaders of half-developed countries with ambitions to seem very important, or, Heaven forfend, the terrorist groups, if they can get their blood-stained hands on the bomb. These are realistic geopolitical anxieties.

Although Greco has followed Auden’s six-part structure and borrowed his catchword, “Anxiety,” the very real geopolitical concerns still with us are not treated in any detail in her poems. Very recently, our current Prime Minister, M. Trudeau fils, was shown on the TV news referring to “anxiety from global turbulence.” Greco’s anxiety is by contrast low-key. But many of these poems are bright with vivid imagery and finely cut lines. So what are her “practical anxieties”?

In the first section, “A String of Worry Beads,” the opening poem “Oh Dear Angel” presents us with the children’s book characters Dick and Jane, but while all seems normal, their dog is agitated and their guardian angel disquietingly “holds in her fingers a thick cigar, the tip of it hottest orange” (p. 3). We are left to surmise on the dangers of our world for a new generation. In her “Land of the Sugar Plum Fairies” she evokes the fears of a child at bedtime, trying to sleep, but tormented by the idea of her heart as a beating walnut which must be placed within a snowman. Such strange fears are a part of many a childhood, as are injections into the arm by a doctor, “Doc Robin” in her book. A more sinister, unnamed fear, arrives in “Geneses” where her meeting with her cigar smoking uncle ends with “… and I believed.”

Real anxiety, though, is conveyed in the plight of the hidden boy in “Don’t Tell” who cannot escape his hiding place when all the other kids go home. The thoughtless cruelty of children is conveyed vividly also in “Chasing the Light of Fireflies.”

A prose poem, “Cheese Leg,” has vivid images and deals with the child’s fear and dislike of butchers and their shops. As someone who had to learn retail butchering from the age of twelve until I was hauled away into the armed forces at age eighteen, I see this piece as stereotyping the butcher’s shop. The voice is that of a post-war pampered generation who could buy as much meat as was needed and drive away with mom in, luxury of luxuries, the family car. Greco doesn’t tell us whether she ate the meat her mother bought from “loud laughing” butchers in the shop whose smell she couldn’t cope with! Has Greco’s growing girl any sympathy for workers who have to face unpleasant jobs every working day? The final poem in this section on childhood, “Chinook,” depicts a girl facing “the red mistake,” her first period.

The second section, “The Mathematics of Anxiety,” deals with mundane and adolescent worries, such as weight problems. In “The Uncertainty of Machines” she frets at sinister dangers (plumbing nightmares) that I think of as funny, the “change of faucets being reversed,/ installed by left-handed plumbers in a hurry” (p. 19). I am glad I am left-handed myself. It’s a bit of an advantage when playing tennis, badminton, or squash against the right-handed.

In “Big Plans” she thinks of a next life in which she will be a plumber. She doesn’t mention whether she’ll be right- or left-handed but the poem finds at its end a disturbing image, “those taps drip-dripping/ deep inside your skull” (p. 95). Where Greco is fearful of her motor mower in “Hazardous,” I think she’s lucky to have one and a lawn to mow! Many B.C. youngsters today will never be able to afford to buy a house on its own lot.

Meanwhile she is “…overanxious over trying/ to quit smoking…” (p. 21). I could go on listing and pooh-poohing these anxieties of a bourgeois Canadian in a vast country thousands of miles away from the horrors of Africa, the Arab world, and that major terrorist target, Paris (France, not Texas). I could notice her off-hand reference to the fathers of children “…the year we all got pregnant/ with somebody’s baby” (p. 93). Instead I now want to look at the quality of the poems as poetry.

In “Regenerative,” her art as a poet makes us feel the experience of planting bulbs, “each oniony shape,” but there is a moment of uncertainty in the language of the poem. In the second quatrain there is the “conviction that green tips will again suffice.” Suffice? Surely she means “surface,” the word she uses in the last quatrain where “they will surface towards earliest warmth”? (p. 92). It could be a mere typo, but if she really means “suffice” we wait to find out how green tips will “suffice” for what?

This uncertainty causes a bit of reader anxiety. And this reader’s anxiety is aroused by linear verse that lacks music. When verse lacks word music, my reaction is to call it unpoetic verse. In “The Importance of the Bird,” Greco has a list of exquisite things the bird is, but I think her last lines protest too much: “The bird is more than all that matters,/ bird knows sky” (p. 75).

No, it is not more than all that matters. This is a sentimental over-statement. If I saw a bird swooping on a baby in the open air, for example, I would not think the winged predator more than all that matters. I would frighten the bird away to protect the baby. But many of the poems are elegantly poised, as is “Full Moon, April,” where the moon is so bright she can hear it. This Rimbaud-like confusion of the senses works very well.

Her sequence in ten sections, “River of Salmon, River of Dreams” has an attractive fluidity, using a simple vocabulary in which the fish word “milt” appears like a prophecy. Sometimes, as in “Lakeside, Summer Afternoon” she is an accomplished imagist, when she ends the poem with rain hitting the lake to make “tiny wet stalagmites,/ pointing toward sky” (p. 85). In “Even the Starship Enterprise is Being Grounded,” Greco raises the major anxiety of our time, “I worry they’ll remember us/ for ruining the planet…” (p. 78).

There are many very good poems in this volume, some of them prose poems, like “Heaven is Some Place and no Place we Know” (p. 35). But in “Wordsong” she has a poem in brief verse couplets and produces herself “a thing so true/ as morning light” (p. 91).

For me, her best poem, so finely attuned to human experience, is “Prep talks” where we encounter the aged and dying mother without sentimentality but in verse that delivers true feeling and experience: mother

tells me she’s been having long discussions with my dad

my son remarks he hopes

they get along a little better

with shining eyes she tells us

she’s ready to go, hears the rustle,

wings about to unfurl (p. 88)

This I would vote for as the best in the collection.

In “My children still bring prizes for my birthday,” Greco tells us that her children bring her flowers picked from local spots as presents, for “They know that I have everything I could ever need/ so now they bring me flowers” (p. 79). She remembers them as small children bringing dandelions. I don’t worry very much about the anxieties of Heidi Greco now that I know her grown up children don’t seem worried about a mom who has everything she could ever need.

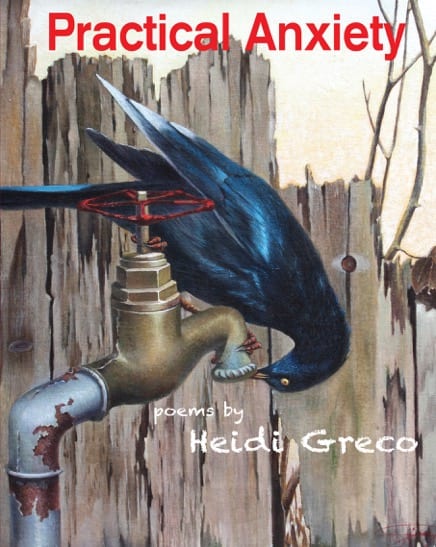

As a book, Practical Anxiety has a wonderful cover of a bird in a parched place where even the tap is dry. The poems are followed by sparse notes, but though she mentions 1432 (near the date of Joan of Arc’s martyrdom), the notes never refer to the date or unlock its significance. Tant pis. Dommage. Among the back cover publicity quotes, I find Anne Simpson and Catherine Owen say just what is needed. I look forward to seeing what Heidi Greco will publish next.

Tom Sandborn –

Three recent volumes show Canadian poetry is still alive, if highly subsidized

Practical Anxiety by Heidi Greco

reviewed by Tom Sandborn

Vancouver Sun – December 21, 2018

https://vancouversun.com/entertainment/books/book-reviews-three-recent-volumes-show-canadian-poetry-is-still-alive-if-highly-subsidized

Heidi Greco is a Surrey based writer, editor and workshop leader. Her wonderfully titled Practical Anxiety, like Thornton’s work (and Purdy’s, for that matter) moves from carefully observed physical reality to lyrical expression via disciplined, well crafted lines. A sense of place is powerful in all this work, and Phil Hall’s line in his tribute to Purdy could apply as well to Thornton and Greco: “the land’s voice sacred noise/thunder and lightning unlike us.”

inannaadmin –

Double the Pleasure: Heidi Greco’s Practical Anxiety

reviewed by Susan Ioannou – December 2, 2018

http://poets.ca/2018/12/14/review-practical-anxiety-by-heidi-greco/

When Inanna Publications announced Heidi Greco’s newest collection Practical Anxiety, it blurbed that the poems “dwell in the hearth of domesticity”. I was intrigued by the title, especially if the poems might relate thematically to my own life as a suburban mother. As I began to read, I was startled. Greco’s somewhat dark slant was unexpected, but refreshing nonetheless. Even more, the craft of her writing was a joy. Happily absent were the irritating tics that mar too many poems these days: compulsive enjambment lurching line after line down the page; stanzas fitted to an arbitrary pattern with no correspondence to thought development; lazy insertions of the word “how” something looked or felt rather than its precise description; and myopic proliferations of details too private for anyone but the author to grasp. In contrast, Greco’s poetry was precise, concise, solid, yet sparkling. She could write about penguins on Mars, and I would enjoy her lines simply for their art.

In the opening section A STRING OF WORRY BEADS, the anxiety of the book’s title becomes clear. These are not sunny memories of childhood, but tap into uneasiness and risk. To underscore such feeling, many of the poems avoid resolution and are left open-ended. For example, in “Oh dear angel”, as the father’s car backs down the driveway, panic flashes. Will he run over little Dick and Jane? Or just in time, will the “pink-gowned guardian angel…Looking bored” redirect her attention from her “thick cigar, the tip of it hottest orange”? We are purposely left hanging. As well, usually pretty children’s images are turned upside down. In the dreamed “Land of the Sugar Plum Fairies”, the fairies with “purpled / skin like a deepening bruise” are “waiting in their tutus to leap onto the covers, grab me.” Equally ugly, reality haunts children in other poems: a brother stillborn; a “carpet of black” flies “spreading germs”; a refrigerator abandoned in a field that might conceal the corpse of a boy; and small kids who tried to house and feed fireflies in a bottle growing into teenagers who ripped the bugs apart to smear on their jeans.

The next section THE MATHEMATICS OF ANXIETY extends this “sinister danger” into adulthood. Greco focuses closeup on domestic fears such as the unpredictability of lawnmower blades and the windowpane death of a hummingbird, all capped by health worries about blood in morning pee, twitching under an eye, and a hardening under the skin “somewhere lurking nasty, out of sight”.

GOOGLING FOR JESUS gives an uneasy twist to religion, “all those bits of heaven right between the eyes”, the final phrase eerily echoing a murderous bullet wound. However, in “Heaven is someplace and no place we know”, the speaker at least “takes solace from cutlery.”

Midway through the book, EARTH AS IT IS expands Greco’s vision into the realm of nature. “If a tree falls in the forest, I know before I hear it. / Connected, I bleed for it inside.” Now much of the imagery takes on a more lyrical quality, as in the beautiful lines “possible rain // coolness to bless us, kiss / the parched mouth of earth.” But the anxiety is still there in her contrasting what nature ought to be with its human desecration:

I know these trees will probably be mashed to pulp for paper –

throw-away diapers, toilet tissue, folding dollar bills,

or nothing more substantial

than flimsy words like these, light enough

to float on wind, disappear in a whim of flame.

INTO THE LIGHT at last introduces moments of serenity and quiet optimism.

The full moon in April is so bright

I can hear it – like a note

sung with your fingers

sliding around the edge

of a glass half-filled with water

its tone long and clear

cool and blue

By the final section MOUNTAINS TO CROSS, even death is treated with tenderness. Greco writes about her mother:

with shining eyes she tells us

she’s ready to go, hears the rustle,

wings about to unfurl

The anxiety of earlier years has given away to a belief

that every holy bud will ripen as it rises, open

its blushing mouth, sing praises to the light, reassure my waning faith

in hope and second chances, reaffirm the promise of springtime.

As well as the thematic ascension from anxiety to relative peace, what makes these poems so compelling is Greco’s mastery of language. Her lines are tight, every word counts. Note the vigour of her verbs in “Relentless” and the attention to detail.

The day the tide rose, it swallowed the beach slowly

then crept along the bricks of the city promenade

fingered its way across the road, insinuating salty paths

between flower beds, lawn trolls, banks of tended roses.

Her imagery illuminates. Consider these examples from “River of salmon, river of dreams”: “she laid her cache of eggs in the secrecy of gravel”; “bony hands of wild salal”; ”remembering / promises made. They flick their tails, / swish off, dive deep, energy renewed”; and “sides as bright as if aflame, blood-ruddy”. As well as pictures, she evokes sounds: “a name / with zing of salty tang: sailfish, saltman, salmon” and “the salmon run assembles // a horde of silvery murmurings”. Elsewhere, my favourite example for its sound effect is “the light-slicked surface of rain-rinsed streets”. The repeating “s” sound makes the splashing audible.

Nor has Greco ignored the sense of touch. Describing an autumn leaf in “On the wane”, she offers lines tactile enough with harsh “c” and “r” sounds to make fingers curl:

it basks in scarred light

cast by the cratered moon

each crevice reflected in ridges

of its own veined skin.

“Morning Commute, Vancouver” even gives personification a twist. Greco describes both humans and fish in terms of each other, as a salmon

…swims along the freeway

beside the rest of us of the working-class fish, climbing

corporate ladders, half past six.

On a larger scale, Greco’s layout on the page, be it the extension of a line, or the shape of a whole stanza, visually reflects, and so supports, both rhythm and the advancement of thought. Even the structuring of the entire book, from anxiety to calm, and from childhood through adulthood, death, to “my next life” is satisfying in its parallelism.

But I do take issue with Greco on one point. Her concluding lines in “The poem I am not going to write” insist “the books deserve better / poems than I can write today.” I respect her humility, but dispute the words’ veracity, for what she has published as Practical Anxiety is already of the best order and an inspiring demonstration for all who would improve their own art.

Andrew Parkin –

Practical Anxiety by Heidi Greco

reviewed by Andrew Parkin

Canadian Poetry Review – February 20, 2019

https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=1625198664279091&id=548677701931198&__tn__=K-R

Heidi Greco is known already from her previous books of poetry, notably those about Amelia Earhart, A: The Amelia Poems (Lipstick Press, 2009) and Flightpaths (Caitlin, 2017). I enjoyed her live reading from these books in New Westminster last year. Her latest book of poems, Practical Anxiety, is in six parts or sections; this suggests that Greco has read Auden’s Age of Anxiety (1947) that was organized into six “eclogues.” In fact, she quotes from Auden’s book as a sort of preface to her own: “The gods are wringing their great worn hands/ For their watchman is away, their world engine/ Creaking and cracking.

Auden’s title is as striking as those lines recalling the enormous worry of the bare survival of civilization: survival after two world wars and the invention and use of the atomic bomb, linked to the new menace of the communist dictator Stalin’s possession of atomic secrets given to the Soviets by the ideologically motivated scientist spies. The constant anxiety during the “Cold War” has now faded, even with the old KGB man, Mr. Putin, in charge of Russia, territorially the largest country on earth; yet anxiety remains about the possible use of atomic weapons by the leaders of half-developed countries with ambitions to seem very important, or, Heaven forfend, the terrorist groups, if they can get their blood-stained hands on the bomb. These are realistic geopolitical anxieties.

Although Greco has followed Auden’s six-part structure and borrowed his catchword, “Anxiety,” the very real geopolitical concerns still with us are not treated in any detail in her poems. Very recently, our current Prime Minister, M. Trudeau fils, was shown on the TV news referring to “anxiety from global turbulence.” Greco’s anxiety is by contrast low-key. But many of these poems are bright with vivid imagery and finely cut lines. So what are her “practical anxieties”?

In the first section, “A String of Worry Beads,” the opening poem “Oh Dear Angel” presents us with the children’s book characters Dick and Jane, but while all seems normal, their dog is agitated and their guardian angel disquietingly “holds in her fingers a thick cigar, the tip of it hottest orange” (p. 3). We are left to surmise on the dangers of our world for a new generation. In her “Land of the Sugar Plum Fairies” she evokes the fears of a child at bedtime, trying to sleep, but tormented by the idea of her heart as a beating walnut which must be placed within a snowman. Such strange fears are a part of many a childhood, as are injections into the arm by a doctor, “Doc Robin” in her book. A more sinister, unnamed fear, arrives in “Geneses” where her meeting with her cigar smoking uncle ends with “… and I believed.”

Real anxiety, though, is conveyed in the plight of the hidden boy in “Don’t Tell” who cannot escape his hiding place when all the other kids go home. The thoughtless cruelty of children is conveyed vividly also in “Chasing the Light of Fireflies.”

A prose poem, “Cheese Leg,” has vivid images and deals with the child’s fear and dislike of butchers and their shops. As someone who had to learn retail butchering from the age of twelve until I was hauled away into the armed forces at age eighteen, I see this piece as stereotyping the butcher’s shop. The voice is that of a post-war pampered generation who could buy as much meat as was needed and drive away with mom in, luxury of luxuries, the family car. Greco doesn’t tell us whether she ate the meat her mother bought from “loud laughing” butchers in the shop whose smell she couldn’t cope with! Has Greco’s growing girl any sympathy for workers who have to face unpleasant jobs every working day? The final poem in this section on childhood, “Chinook,” depicts a girl facing “the red mistake,” her first period.

The second section, “The Mathematics of Anxiety,” deals with mundane and adolescent worries, such as weight problems. In “The Uncertainty of Machines” she frets at sinister dangers (plumbing nightmares) that I think of as funny, the “change of faucets being reversed,/ installed by left-handed plumbers in a hurry” (p. 19). I am glad I am left-handed myself. It’s a bit of an advantage when playing tennis, badminton, or squash against the right-handed.

W.H. Auden, Age of Anxiety (1947)

In “Big Plans” she thinks of a next life in which she will be a plumber. She doesn’t mention whether she’ll be right- or left-handed but the poem finds at its end a disturbing image, “those taps drip-dripping/ deep inside your skull” (p. 95). Where Greco is fearful of her motor mower in “Hazardous,” I think she’s lucky to have one and a lawn to mow! Many B.C. youngsters today will never be able to afford to buy a house on its own lot.

Meanwhile she is “…overanxious over trying/ to quit smoking…” (p. 21). I could go on listing and pooh-poohing these anxieties of a bourgeois Canadian in a vast country thousands of miles away from the horrors of Africa, the Arab world, and that major terrorist target, Paris (France, not Texas). I could notice her off-hand reference to the fathers of children “…the year we all got pregnant/ with somebody’s baby” (p. 93). Instead I now want to look at the quality of the poems as poetry.

In “Regenerative,” her art as a poet makes us feel the experience of planting bulbs, “each oniony shape,” but there is a moment of uncertainty in the language of the poem. In the second quatrain there is the “conviction that green tips will again suffice.” Suffice? Surely she means “surface,” the word she uses in the last quatrain where “they will surface towards earliest warmth”? (p. 92). It could be a mere typo, but if she really means “suffice” we wait to find out how green tips will “suffice” for what?

This uncertainty causes a bit of reader anxiety. And this reader’s anxiety is aroused by linear verse that lacks music. When verse lacks word music, my reaction is to call it unpoetic verse. In “The Importance of the Bird,” Greco has a list of exquisite things the bird is, but I think her last lines protest too much: “The bird is more than all that matters,/ bird knows sky” (p. 75).

No, it is not more than all that matters. This is a sentimental over-statement. If I saw a bird swooping on a baby in the open air, for example, I would not think the winged predator more than all that matters. I would frighten the bird away to protect the baby. But many of the poems are elegantly poised, as is “Full Moon, April,” where the moon is so bright she can hear it. This Rimbaud-like confusion of the senses works very well.

Her sequence in ten sections, “River of Salmon, River of Dreams” has an attractive fluidity, using a simple vocabulary in which the fish word “milt” appears like a prophecy. Sometimes, as in “Lakeside, Summer Afternoon” she is an accomplished imagist, when she ends the poem with rain hitting the lake to make “tiny wet stalagmites,/ pointing toward sky” (p. 85). In “Even the Starship Enterprise is Being Grounded,” Greco raises the major anxiety of our time, “I worry they’ll remember us/ for ruining the planet…” (p. 78).

There are many very good poems in this volume, some of them prose poems, like “Heaven is Some Place and no Place we Know” (p. 35). But in “Wordsong” she has a poem in brief verse couplets and produces herself “a thing so true/ as morning light” (p. 91).

For me, her best poem, so finely attuned to human experience, is “Prep talks” where we encounter the aged and dying mother without sentimentality but in verse that delivers true feeling and experience: mother

tells me she’s been having long discussions with my dad

my son remarks he hopes

they get along a little better

with shining eyes she tells us

she’s ready to go, hears the rustle,

wings about to unfurl (p. 88)

This I would vote for as the best in the collection.

In “My children still bring prizes for my birthday,” Greco tells us that her children bring her flowers picked from local spots as presents, for “They know that I have everything I could ever need/ so now they bring me flowers” (p. 79). She remembers them as small children bringing dandelions. I don’t worry very much about the anxieties of Heidi Greco now that I know her grown up children don’t seem worried about a mom who has everything she could ever need.

As a book, Practical Anxiety has a wonderful cover of a bird in a parched place where even the tap is dry. The poems are followed by sparse notes, but though she mentions 1432 (near the date of Joan of Arc’s martyrdom), the notes never refer to the date or unlock its significance. Tant pis. Dommage. Among the back cover publicity quotes, I find Anne Simpson and Catherine Owen say just what is needed. I look forward to seeing what Heidi Greco will publish next.

Renée Knapp –

Practical Anxiety by Heidi Greco

reviewed by Natasha Sanders-Kay

subTerrain issue #83 – January 2020

http://subterrain.ca/reviews/169/practical-anxiety

Practical Anxiety is a book of wonders and dreams, questions and calls to action, meditation, eulogy and prayer, sometimes with all of these elements acting at once. The title offers multiple meanings: there are anxieties about the practicalities of the everyday — bills, traffic, Jell-O sticking to the wall of a fridge; then there are more looming fears that are arguably practical to carry, practical as in necessary, like fearing for the disappearance of caribou and salmon, clean waters and forests. From religion, politics, class injustice and climate change to gender and relationships, ageing and housework, Heidi Greco dives into anxieties of different kinds, all with breathtaking results — breathtakingly beautiful and breathtaking like a panic attack.

While panic pulses throughout the collection, Greco gives us glimmers of hope, as in “Beatitudes for the 21st century,” where the spirits of recyclers “shall dwell in trees,” where the “sweet-natured . . . shall come back as bees.” There is also plenty of humour — “Truthfully, he looked like a bit of a goof. But a nice one,” says the speaker in the most lovable depiction of God I’ve ever encountered. In another poem a woman is irked by a comment from her partner and channels her rage into washing dishes, takes “solace from cutlery . . . considers the / relative uses of knives, wielders of final pronouncements.” This piece is an anthem I intend to display by my kitchen sink!

There are just a couple of spots where I could’ve used smoother transitions, but for the most part this collection is impeccable. The language used to describe the natural world is the perfect language with which to describe the writing itself: each word and its placement is like the salmon laying her eggs “in the secrecy of gravel,” each “private stone” carefully selected. As a reader I’m pulled into the poems’ pounding current, so that I too am swimming in a dream, “thrusting my body upward / hurling myself, stretching, / to climb the watery structure, / falling back again, / again, / again.” Greco’s voice is the moon she writes of, its “pale light a beacon to be learned,” with a “tone long and clear / cool and blue.” Her poems are “trees that rise / high as guiding stars, sprawling constellations to point the way.”

Greco rescues the text from preachiness by incriminating herself in some of the poems. She mourns for murdered trees “mashed to pulp for paper” to be used for “nothing more substantial / than flimsy words like these, light enough / to float on wind, disappear in a whim of flame.” She is gifted an African violet she “will surely kill by June.” Driving past a male hitchhiker who “should have his own car, his own stink of fuel,” her thoughts turn to roses in snow, cold “against that white, pink as lonesome thumbs.”

Impressive is the author’s attention to anxiety at different ages. There are childhood fears of sinister sugar plum fairies, mean butchers and schoolkids, then there are adults who keep their pantries overstocked for disasters. There’s “the brown-haired girl, sitting / in the toilet stall, looking / at the red mistake / smeared on her underpants” as well as the adult with “[p]inkest strains of maybe-blood in yesterday morning’s pee.” There is the woman who must bid her mother goodbye and the one who studies older bodies in the pool’s change room, coming to recognize different surgical scars, copies the women’s careful movements, “these subtle choreographies.” Nightmares have no age limit, they continue in images of polar bears like fish, “swarming in a sea gone soupy warm,” “swirls of purple starfish / adorned with too many arms, crabs who run insane / as if their heads have been chopped off, / churning spirals of ever-tightening circles.” A nursery rhyme tails a salmon’s journey to estuary, “where river meets the sea / and ocean rises, rinsing itself, merging wet worlds.”

Practical or not, anxiety’s never looked so gorgeous.