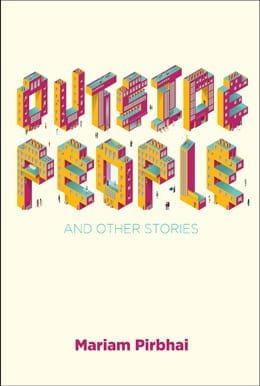

Winner, American Book Fest 2019 Best Book Awards

(Fiction – Short Story)

Finalist, American Book Fest 2019 Best Book Awards

(Fiction – Multicultural)

Finalist, 2019 International Book Awards

(Fiction – Short Story)

Finalist, 2019 International Book Awards

(Fiction – Multicultural)

Winner, 2018 IPPY Gold Medal for Multicultural Fiction

A Haitian woman survives the ravages of an earthquake only to find her sister, an émigré in Montreal, the subject of a grisly crime. A chambermaid in a Mexican tourist resort frequented by Canadian tourists wonders why all the men in her life seem to leave her for distant lands. A Jamaican migrant worker at an Ontario chicken farm comes to the aid of his Peruvian co-worker on the eve of a fatal car accident. And a young Pakistani-Canadian woman finds herself in the midst of a protest march defending Muslim women’s rights on the same day she has agreed to meet her Moroccan lover. The diverse cast of characters that energize Mariam Pirbhai’s Outside People and Other Stories not only reflects a multicultural Canada but also the ease with which this striking debut collection inhabits the voices and perspectives of nation, hemisphere, and world.

“With clear-eyed compassion, generosity and literary brilliance, Mariam Pirbhai has deftly illuminated characters whose lives in literature are usually relegated to the shadows of the mainstream. In doing so she has given much needed, long-overdue breath to a cast of characters who create the landscape even as they have been, until now, invisible in it. As Diane Arbus is to photography, so is Mariam Pirbhai to literature—bringing forth the margins, but nobly, with understanding and an unusual generosity in her handling of contemporary society’s machinations.”

— Shani Mootoo, author of Cereus Blooms at Night and Moving Forward Sideways Like a Crab?

“What a stunning debut this collection, Outside People and Other Stories, is for Mariam Pirbhai. These stories transport us into the lives mainly of newcomers to the Canadian landscape. The broad range of characters includes first-and second-generation Canadians, new citizens, temporary workers and even a worker in a resort in Mexico that caters to numerous Canadian clients. The power of the stories lies in the author’s success at capturing the worlds of the marginalized and racialized so vividly, with such understanding and compassion, that we cannot ignore or dismiss their humanity. Indeed, we are enriched by it. This book deserves a wide readership.”

— Mary Lou Dickinson, author of Would I Lie to You? and The White Ribbon Man

“With intelligence and command of her craft, Pirbhai invites us into the lives . . . of the émigré and following generation(s): from Pakistan, India, Morocco, Jamaica, Mexico, Japan, Philippines, Haiti. As a result of the portability of technological skills, rapid global communication, and mobility across continents, “outside people” find themselves in a state of displacement and . . . sense their “otherness” as perceived through the eyes of others. Outside People and Other Stories views the world and humanity through a wide-angled lens. Give it a read. It will both entertain and enlighten.”

—Rhoda Rabinowitz Green, author of Aspects of Nature

Mariam Pirbhai is the author of a debut short story collection titled Outside People and Other Stories, which won the 2018 IPPY Gold Medal for Multicultural Fiction, and was ranked among CBC’s top ten recommended “must read” lists of 2017. Her short fiction has appeared in numerous anthologies and journals, including Her Mother’s Ashes: Stories by South Asian Women in Canada and the United States Vol III, Pakistani Creative Writing in English, and the Dalhousie Review. She is Professor of English in the Department of English and Film Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University, where she specializes in postcolonial and diaspora studies. She was born in Pakistan and lives in Waterloo. More information available on her website: http://www.mariampirbhai.ca

From “Toronto’s Dominions”

Sure, Arjun’s parents had tried to sweeten the deal like condensed milk drizzled on a saltine cracker. They had generously offered to waive her dowry, a custom that her uptight cousin in Vancouver referred to as the reason why millions of female fetuses ended up in Indian landfills, but which Lata thought of as an unimpeachable tradition designed precisely to protect a woman’s worth. Her father refused the offer, but begrudgingly made a show of accepting the Malhotras’ contribution to other matrimonial expenses. Still, by Lata’s calculations, a Toronto wedding paid for in dollars (while Canadian and American currency were on par, to boot!) versus a Delhi reception paid for in rupees hardly made for a fair rate of exchange. At least her gifts, which included a mini Fort Knox of gold coins (the new alternative to the conventional bangle set), was some compensation for the gross depreciation of what her father fondly referred to as his “best loved investment portfolio.” But then again, her father could not have foreseen, nor would he be able to compute, the extent of his recent miscalculations. Only Lata could project future contractual demise without the cushion of enough hurricane bonds to ride her through this emotional tempest. Only Lata could see bullion and bangles resold (though admittedly the gold market had never been hotter), and dreams of prime real estate holdings in Credit Mills forfeited, in the dissolution of a marriage that would bear little yield in terms of present family interests or future family gain.

For once she had seen the value in home-grown and home-spun and this is what she had to show for it! He played a good game but Made in India he certainly was not! He had said the requisite amount of pleases, thank yous and namastes to her parents. He had appeared adequately enthusiastic without being inappropriately desperate at the prospect of his Canadian bride-to-be. And his web-profile photos, which Lata had found particularly appealing, weren’t airbrushed or doctored in any way (she knew this because she hired a fashion photographer to scrutinize them). And for all that, something had gone terribly wrong in the voyage across. Arjun was like one of those disappointing shipments of grown-for-export mangoes: touted as nothing less than the Alfonso, the king of the mango, when in reality he was as green and sour as the inferior kind used for pickles and chutneys.

Giving up on the unrelenting gear shift, Lata sat in her car and replayed their “talk” over and over in her throbbing but perfectly butterscotch-highlighted head of hair. And to think that all she’d said was that it was time to start a family.

“An heir! You want an heir! You can’t have an heir without an inheritance!” he jeered, and stormed out of the house to catch the eight a.m. bus, which he insisted on taking because it allowed him to connect with the people. Lata may not have understood her husband’s desire to connect with the people, or who exactly “these people” were, but it didn’t take an expert to figure out that she had been struck out by a curve ball aimed and fired, with barbaric accuracy, at her total net worth.

Lata’s first instinct was to scold her parents for not having done a thorough background check on the Malhotra family. Weren’t they supposed to come from a long line of well-placed Delhi stock? Wasn’t Arjun’s great-grandfather supposed to be related to that Nehru guy? Or one of those people her abbu-ji droned on about, lapsing into languorous bouts of nostalgia for what he called the “days of york” or “yoda” … or whatever the hell those days were. At any rate, those kinds of connections didn’t interest her. In her fragmented and scant conception of Indian history, Mohandas K. Gandhi and Indira Gandhi were some famously unfashionable married couple, and “Partition” was a bad word whose mere mention launched her parents into frenzied exchanges of Hindi or a complicit silence that only a long distance call or news of relatives could break.

At any rate, the real injustice was not the suspect nature of Arjun’s lineage. She had wanted to say as much when she called her parents earlier that day. Not in the mood to endure a lecture, Lata only managed to mumble something about their needing to be prepared to take some responsibility for this Hungama before she, herself, hung up. Apparently her mother didn’t dwell on the cryptic or frantic nature of the call, otherwise Lata would have been bombarded by ariatic voice messages all day long: “What is all this nonsense, beti?” or “How dare you hang up on your mother!” or the classic, “What will your father say?”

In retrospect, even her mother’s tirades would be a welcome intrusion if it meant being able to confide in someone. She wasn’t able to concentrate on much else anyway. She was desperate to confide in one of her co-workers but Lata had vowed, from what seemed to be her kindergarten days, to keep her Indianness, and everything that was remotely connected to it, where it belonged: in the haldi-infused walls of her mother’s kitchen. In this she was sorely out of step with the times because, in fact, there was nothing hotter or cooler than being Indian, at least when it came to food and fashion. If she were a silk scarf, a beaded “tunic” or a foodies’ secret ingredient in one of those Top Chef cook-offs, being Indian wouldn’t feel so lame. But even in the category of consumable India, she felt like an outmoded spice-mix packet for some generic dish (Vindaloo or Chana Masala) upstaged by the fusion-inspired Naan pizzas or just-add-water exotic Tamil soups.

In spite of this, or maybe because of this, everything about Lata’s life, except her arranged marriage, was a testament to her judicious adherence to North Ameri-khana (a bilingual pun that Arjun had invented in his mimicry of her decidedly un-ethnic eating habits, which generally consisted of boxed greens accompanied with broiled chicken breast or baked salmon). All her daily lifestyle choices were motivated by her desire to emulate the signs and symbols of a thoroughly Canadian existence that did not require the numerous accommodations of multiculturalism or political correctness. For this reason, the only person outside community circles who was privy to what Lata cryptically referred to as “the details” was her best friend Vanessa. And Vanessa had only found out because her mother once saw fit to entertain her with stories of the various “duds” they had rejected from the matrimonial websites. “I’m sorry?” Vanessa had interjected, always a little discomfited by Lakshmi Menon’s accent. “Duds, beti, duds!” her mother persisted.

“You mean dudes, Mrs. Menon?” Vanessa looked perplexed.

“No, duds, Vanessa dear! It’s an Eng-u-lish word for … loos-ah.” her mother clarified, pleased with her efforts at crossing this idiomatic and generational hurdle.

Vanessa took a few minutes to decipher her mother’s explanation: “Ooooh, you mean a loserrr?” Lata almost died having to sit through those excruciating eleven minutes till her mother shuffled off to tend to some household chore.

For everyone else, Lata had spun, with minimal gesticulatory verve (she was very conscious of the fact that Desis spoke with their hands), a mundanely credible fairy tale about meeting Arjun at a trendy nightclub in Delhi during a summer vacation. “First it was a summer fling. Nothing more,” she’d breathlessly explained to Jennifer and Becky, the bank tellers she usually had lunch with. “But even with an ocean between us, we couldn’t stop thinking about each other.… ” Everything but the wedding details was sheer fabrication, of course, details which, in this case, Lata described with gusto, throwing in, for added visual effect, a few gratuitous comparisons to her ever-growing list of wedding-themed chick flicks: My Best Friend’s Wedding, Wedding Planner, 27 Dresses, Something Borrowed. Not that Jennifer or Becky needed any cinematic assistance in imagining the scope, scale, and expenditure of a respectable wedding. Working at the bank was exposure enough. So many young couples were in debt because of their “big fat weddings” that one of the rotating managers had designated it a new type of “unsecured loan.”

As for the divorce Lata was now bracing herself for: well, now there was a fine North American tradition she could participate in without any need for creative dishonesty. Maybe it would even help her bond with Jennifer, who was a twenty-something divorcée and single mother of two. Maybe divorce would give her the kind of edginess that twenty-somethings were supposed to emulate. She didn’t know what classified as edgy, but she was convinced that making a mess of one’s life was a sure step to gaining “street cred,” a term she had picked up watching some reality cop show with her younger brother Sanjay.

Still hesitant to confide in Jennifer or Becky because of the million and one questions it might generate, Lata thought of Priya, the bank receptionist. In normal circumstances, Lata avoided Priya like the plague, but desperate times called for desperate measures. For one, Priya was the only one of her co-workers to have met Arjun. Lata recoiled from the memory. She had almost dropped the iPhone she was browsing with one hand, her custom-monogrammed water thermos in the other, when she saw Arjun and Priya chatting up a storm in the parking lot. To make matters worse, the two of them were speaking in Punjabi. Lata had no idea Arjun spoke Punjabi! She remembered being impressed by the fact that he had checked off the “fluent in multiple languages” category on his marital profile, which she assumed meant French and German, or French and Spanish, but as it turned out merely consisted of Hindi, Punjabi, and English. Another act of false advertising, Lata thought resentfully.

inannaadmin –

The people we often forget – Outside People and Other Stories, Mariam Pirbhai.

reviewed by Noah Page

The Fiddlehead (spring, issue 275) – May 2018

Excerpt

Mariam Pirbhai’s debut short story collection Outside People and Other Stories features nine stories with protagonists from throughout the world. Pirbhai packs an impressive amount of settings into the collection, including a Mexican tourist resort, Haiti after the 2010 earthquake, and a chicken farm in southern Ontario. The wide range of settings and characters helps to keep these stories stimulating by continually bringing the reader into new situations and scenery. Contrary to the diversity in locales, Pirbhai’s characters often share some common traits. In her stories set within Canada, the characters are usually racialized immigrants who are subtly reminded that they will never be considered fully Canadian by the established population. For the stories set outside Canada, the people depicted struggle to develop lasting familial relationships as their family and friends jump from place to place attempting to find work. As an academic with a number of books on postcolonial studies and a professorship at Wilfred Laurier University, Pirbhai shows her meticulous understanding of the issues faced by immigrants throughout the world. She builds her stories on the base of these issues, but doesn’t sacrifice characterization in favour of merely illustrating their struggles. Instead, she demonstrates how her characters are complex people with pasts, families, homes, and distinct personalities, successfully using her knowledge to create narratives where personal lives and political circumstances overlap. With an efficient and direct style that favours agile pacing and short sentences over ornate description, Outside People and Other Stories achieves the difficult feat of balancing both political sophistication and emotional energy.

In my mind, the strongest stories in this collection are the ones dealing with the intersection between poor labour conditions and racial minorities. In “Chicken Catchers,” the first story to deal with these themes, Jamaican farm hand Reggie takes care of his ailing Peruvian co-worker Amaru in their shared barracks. The story opens with a dedication to ten labourers who died in a car crash, which Pirbhai states was “one of the worst road accidents in Ontario’s history” (15). “Chicken Catchers” abounds with significant details that help draw out the particularities in the lives of these two workers. The workers’ primary task is capturing chickens to inject them with antibiotics, and

…they had to work so fast that, on more than one occasion,

[Reggie] was quite certain the needle had missed a chicken

and pierced through his gloves” (25).

The small glimpse into these people’s work has the potential to suggest a much wider picture; showing one of the relatively small dangers migrant workers face, made me begin wondering about other risks and abuses they face to feed themselves and their families. The story ends rather suddenly, when a manager from the farm comes to gather the belongings of the men who live at the barracks. As Reggie frantically attempts to discern why she seems to be stealing these items, the manager unsympathetically says, “There was an accident this morning. A truck hit the van…Worst crash of its kind around here. Only one survivor” (30). The abrupt ending here mirrors the abrupt ending of the men’s lives, and the manager’s careless ransacking of the barracks shows how little respect is granted to racial minorities and the working class even after tragedy befalls them.

The next story, “Corazon’s Children,” possesses a similar thematic concern about labour and racialized people, but imagines it in a much more familial context. Here, the eponymous Corazon cleans the house of Mrs. Hartman, a wealthy psychiatrist. The story opens with Corazon cleaning the mantel on which many of Mrs. Hartman’s framed photographs of her and her husband are displayed, though they are free of any pictures of children except for Mrs. Hartman’s niece and nephew. Corazon herself keeps a picture of the children she has left behind in the Philippines and glances at it a few times. By the end of the story, both women seem distant from their families, albeit in different ways.

The protagonist of “Sunshine Guarantee,” Lucita, is in a similar situation as Corazon, but here the tone is more humorous. The story is set in a Mexican resort and follows Lucita as she tidies the guest rooms and reflects on her relationship with a man named Miguel who is constantly moving around as he looks for employment. “Sunshine Guaranteed” contains my favourite minor character in the collection, Angélica, who wonders aloud “Why can’t we value our labour in our currency? Why can’t our currency value our labour?” (65).

Seeing the other side of a tourist resort, where the workers are making vaguely Marxist declarations about their working conditions, really undermines the promise of sun and fun indicated by the story’s title. There is also a moment where a Canadian tourist grabs a bottle of shampoo from Lucita, without a smile or word of thanks. I liked this instance in particular because it broke the stereotype of the polite Canadian. And as it turns out, the hotel workers are refilling the shampoo bottles with a cheap local brand that isn’t really any different from the brand the hotel gives out. But the amusing parts are not the only thing that hold this story up; Lucita and Miguel’s precarious relationship also demonstrates the difficulty itinerant labourers have making meaningful romantic connections and eventually settling down to have family lives.

…Outside People and Other Stories is sizable in its scope, and for the most part achieves what it intends to. Pirbhai’s versatility in style, character, and content generally left me satisfied, and, more importantly, her stories provide valuable reminders about the mistreatment and neglect of the people who keep our society running, and for that alone it’s worth your time to read.

inannaadmin –

Outside People and Other Stories by Mariam Pirbhai

reviewed by The Miramichi Reader – October 21, 2017

http://www.miramichireader.ca/2017/10/outside-people-review/

Mariam Pirbhai was born in Pakistan and lived in England and the Philippines before emigrating to Canada. She lives in Waterloo, Ontario, where she is an Associate Professor in the Department of English and Film Studies, at Wilfrid Laurier University. Her short stories have also appeared in numerous anthologies and literary journals.

Outside People and Other Stories (2017, Inanna Publications) is her debut collection of short fiction. I am fascinated by stories, fictional or otherwise of the immigrant’s experience in coming to a new country and adjusting to the western way of life. Outside People and Other Stories contains nine expertly crafted works of short fiction about such experiences. Told either from the viewpoint of the person in their new country (Canada, in this instance) or from the point of view of the family left behind, we are given a glimpse, albeit brief into the lives and thoughts of such persons, typically from a woman’s perspective. Ms Pirbhai has us peer into the lives of chambermaids, migrant workers, bankers, factory workers, maids, a cancer victim and a Haitian woman whose sister was a victim of a senseless crime thousands of miles away in Montreal.

The Outside People

Some of Ms Pirbhai’s characters are “outside” as respects being outside their native country (the usual case), and outside of their areas of experience and training, such as is the case with Radha Chatterjee, a woman with degrees in English and Education, who cannot get a position in Canada as a teacher:

She understood that a woman in a sari, a long black plait and a red dot on her forehead was not qualified to relate to a roomful of North American teenagers. She understood that in this country her qualifications were no better than a weight around a drowning man’s neck.

That excerpt is from “Crossing Over” my personal favourite of the nine stories here. It is about two couples, one doing well financially (Krishna and Radha), the other (Tariq and Mumtaz) not so much since coming to Canada.

Their vastly different trajectories to the West filled the space between them [Krishna and Tariq] with epic tension, Krishna looking on their migration with unqualified pride and Tariq looking on his with unqualified resentment.

Another favourite was “Sunshine Guarantee” which is the story of Lucita, a chambermaid working in a Mexican vacation resort. Her brother has emigrated to Canada, and her son has met a girl from Guyana and may be moving to Europe with her. Lucita lives with her mother who is suffering from dementia. There’s a lot Lucita doesn’t understand, such as what a sunshine guarantee is. Angelica, a front desk staff explains that the “gringos” expect sun, not rain, when on vacation. If it rains, they get something for free, like a day at the spa or a snorkelling lesson.

“You know how much the gringos love free stuff. Mira: people like you think that nothing good comes for free, and working hard is the only way to heaven. But most people think that because nothing comes for free, heaven must be a place where you get more for less. And Mexico is where the gringos come to get more for less. I bet you didn’t know you’re already in heaven, Lucita. Now you can forfeit next Sunday’s confession and live a little.”

Conclusion

Notable is the fact that each of the nine stories are infused with words and phrases in the storyteller’s native language, adding authenticity and realism to the narratives. There is even a Glossary at the back of the book that translates these for those of us not fluent in Spanish, Hindi/Urdu, French, Arabic, Tagalog and island Creoles. Most refreshing is the fact that Ms Pirbhai has felt no need to tell these stories with any unnecessary profanity or unwarranted adult content. I would venture to say Outside People would be enjoyed by mature young adult readers too.

In short, Outside People and Other Stories is an exceptional group of short narratives that are appealing, insightful and a treat to read. Rhoda Rabinowitz Green, the author of Aspects of Nature, says of Outside People: “Outside People and Other Stories views the world and humanity through a wide-angled lens. Give it a read. It will both entertain and enlighten.” I thoroughly agree, and this collection will go on my 2018 longlist for The Very Best! Awards in the short fiction category.