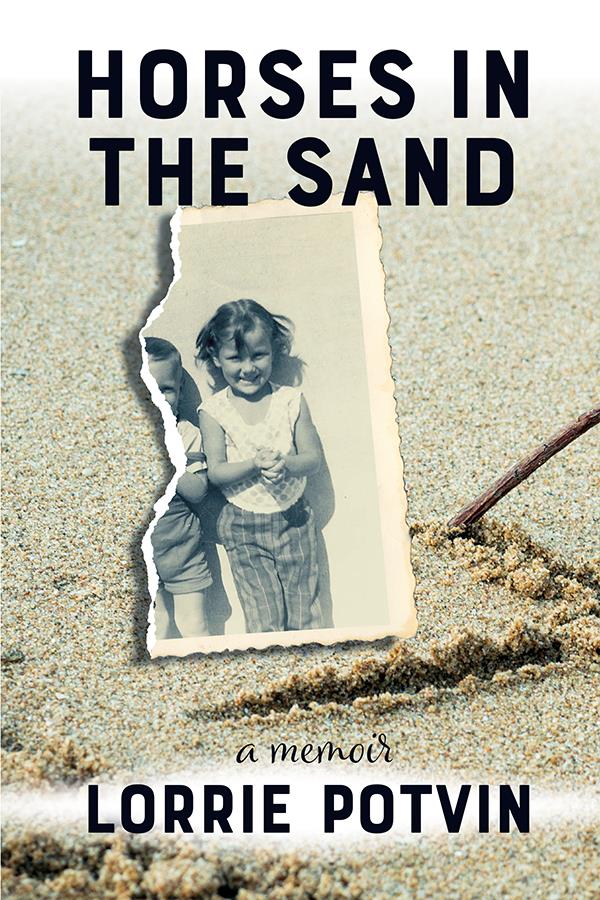

A sequel to First Gear: A Motorcycle Memoir, Horses in the Sand is a collection of stories that document a queer Métis woman’s journey from her sparse beginnings as a child to becoming a tradeswoman, teacher, and artist. With courage, humour, and frank honesty, the stories describe what it was like to grow up as a girl who was starkly different from “normal” and how “coming out” became a lifelong process of self-acceptance and changing identities. Potvin’s tales also speak to the difficulties in participating in and maintaining healthy adult relationships when childhood foundations are rooted in violence and trauma, culminating with a triumphant account of fulfilling a long-time dream of buying land and building a home with her own hands. Ultimately, this memoir is a celebration of making art, telling stories, and of finding her birth father, a family of half siblings, and an Indigenous community whose presence she had always felt, but to which she never knew she belonged.

“Here’s rare and clear-eyed insight, without self-pity, into the complex life of a woman unafraid to have non-traditional dreams and to follow them. What a pleasure to read the story of a woman who has the courage to be all she can be, in the ways she wants to be it, with respect for the people around her and for her trade, but taking no guff. Thank you Lorrie Potvin!”

—Kate Braid, author of Journeywoman: Swinging a Hammer in a Man’s World and Hammer & Nail: Notes of a Journeywoman

“Lorrie’s stories had me laughing and crying. As an Indigenous woman who has had similar feelings and experiences I found her candor and humor refreshing. Stories from our women are certainly needed in a field once dominated by men’s stories.”

—Beverly Little Thunder, Two-Spirit Lakota Elder, author of the memoir One Bead at a Time (2016)

powered by Crowdcast

- HORSES IN THE SAND

I headed south from Deadwood on Highway 385 and stopped to have dinner at the Pactola Visitor Center in the Black Hills National Forest.

I pulled up to the beach area and unloaded my cooler. Skinny Bitch, a shame and guilt expert, laid out cottage cheese, tuna, avocado, cherry tomatoes, and a mixed salad. Skinny Bitch’s sister, Fat Chick, had been dormant on the trip except for the time she made an appearance at Bear’s Paw Bakery in Jasper. When I was in line for a coffee, she kept poking me to look at a ceramic jar on a shelf. Written on its side in block letters was COME TO THE DARK SIDE. WE HAVE COOKIES. Skinny showed up, and we all argued back and forth, irritating each other in line until I got to the counter. We compromised on a berry muffin.

I assembled my salad at a picnic table on the beach and sat down facing the reservoir. The sun was setting on three kids and a black lab playing in the water. From their shouts and laughter, I learned the dog’s name was Bella. She came over to greet me with her tail wagging. She reminded me of Rafter, our very lovable black lab, who Paula and I euthanized right before my trip. That dog followed me everywhere. Whether I was in the house or out on the land, she was there. When I’d put her in the back of the Edge for a drive, she always jumped over into the back seat and sat with her front paws on the floor so she could lay her head on the centre console. I would reach back to pet her head, and her tail thumped the seat repeatedly.

Bella was a little taller and leaner than Rafter, but she had the same sweet disposition. Her tail frantically wagged back and forth, and her hips wiggled in time with its movement. I rubbed her ears and held her head in my hands to look in her eyes before she ran back to the water.

An older, mustachioed maintenance man wearing a ball cap and a light tan work shirt with a park maintenance logo on it walked the beach area in a grid pattern, picking up garbage along the beach. When he came close, I asked, “Is the gate gonna close soon?”

“No. You can stay here all night if you’d like,” he replied without losing a step in his grid walk. I overheard him talking with the woman whose kids were still in the water. They talked camping and touched on the fact that the concession people have all pulled out: “It’s the end of season, and Loop A is still open for camping.”

When he made his way back, I asked him about camping. He told me that I could camp for free. There was no one around to collect the fees, and the lower women’s washroom in Loop A was the only one open. He said there were lots of waterspouts available and that there should be enough firewood down there to have a fire. “Camp there until the Forest Service comes and tells you can’t,” he encouraged. I thanked him and told him I’d go over and check it out. I finished my dinner and packed up the cooler. It was funny how Skinny Bitch and Fat Chick always managed to skip out on the cleaning up part.

I thanked him and told him I’d go over and check it out. I finished my dinner and packed up the cooler. It was funny how Skinny Bitch and Fat Chick always managed to skip out on the cleaning up part.

He continued picking trash and then came back over to me. “Don’t you want to know how to get there?”

“Sure.”

“Up there,” he said, pointing towards his left. “Turn right after about three-eighths of a mile, go past a cove with boats, and then turn right again. Then take your next left, go past the hut—don’t worry about it, no one will be there—go to where the garbage bins are and turn right past them.”

“So, right, right, left, and then right. Is that right?”

He chuckled. “I figure it is.”

I was closing my door when he returned again to give me directions to the gas stations that had laundry facilities, gas, and ice because “it’s good to know where those things are.”

I circled through Loop A and was blessed with a site overlooking the reservoir, Pactola Lake. At an uphill campsite was a Ford Transit with a Vermont licence plate. The couple who emerged were older, lean, and fit. There were two road bikes strapped to a carrier on the back of the van.

Down the hill to the south, at the next site over, were a young couple in their twenties. They had a truck, a boat trailer, and an old canvas tent, the style that used exterior galvanized poles to hold it up. They were enjoying a large fire.

I dressed in warm clothes, started a small fire of my own from scraps of wood that I quickly and easily scavenged from a couple of firepits, and used my headlamp to read a mystery novel I had been meaning to finish. I took the novel to bed around midnight and read until I fell asleep.

It had become a pattern, and not just on the road, that I woke up after three to four hours of sleep. That morning I woke up at four thirty.My mind was circling and looping, full of questions. Where am I going? What should I do? Why am I feeling the need to be on the move? Should I go home? What’s Paula doing? Should I call her again or wait for her to call me?

I read some more and then floated in and out of sleep until six-thirty, when a beautiful sun rose out the back window of the Ford. It was an exceptional sunrise, like a lot that I had witnessed—like a lot we had all witnessed, I suppose—but it didn’t meet the gold standard of the sun setting or rising on the prairies.

I thought I had experienced the most beautiful sunsets over the granite outcroppings and woods of the boreal forest, but my bragging rights were smashed when I saw my first prairie sunset driving west towards Saskatoon. I was awed, and it stirred a deep appreciation of the poems and prose that had been written in an attempt to fully capture the essence of the enduring prairie sun, as elusive as the spirit of the soul.

I hoped the rising sun would bring some needed warmth for the day. It had been a cold night, and I was very happy with my new blanket. I reluctantly got out of bed, layered on clothes, slid out of the Edge and into my boots, put on a jacket, and made some coffee with a percolator on my Coleman stove.

I noticed the young man running to his truck for wood. He used lighter fluid to get a fire going. His partner came out of the canvas tent, and they headed down to the shore along a dirt track, carved out of the ground like a snake winding around rocks and trees. It wasn’t long before I heard a motor start and saw them in their boat heading towards the middle of the lake. He was in shorts and a t-shirt, and she didn’t seem to have much more on herself. They were back within fifteen minutes. I saw her huddled up in the front, and he wasn’t sitting as tall as when they first left.

I finished my mug of coffee, putting the rest from the percolator in a thermos. The biker couple from Vermont were up and dressed in their bike shorts and tops. The young couple, buried in clothes, unhitched the boat trailer, got in the truck, and left. I suspected they might have thought catching and cooking their own breakfast would be kind of romantic, but a hot breakfast in town was a warmer alternative to spending time half-naked in the middle of the lake on a cold morning.

The young man kicked out their fire before they left, and plumes of smoke drifted through my site. I closed the doors to the Ford so my clothes and bedding wouldn’t absorb the smoke—a nod to Paula. She wouldn’t complain, but she always asked me to store the jacket I’d wear, either when keeping the fire for ceremony or burning brush, in the garage and not with her coats in the closet.

During my drive out of the reservoir, I pulled over to where some slate-like stone was exposed. It was the Sioux who called the area Paha Sapa, meaning “hills that are black.” The layers of stone were dark grey, and the ponderosa pines looked like they had been touched with charcoal along their bark edges and limb knots. The hills were also known to the Sioux as Wamakoagnaka E’cante, or “the heart of everything that is.”

I picked up a piece of stone and laid a pinch of tobacco down in its place before getting back into the Edge. I was taught by an Elder that when you take something from Mother Earth, you should offer tobacco in return because “tobacco medicine teaches us about reciprocity.” I stopped at the Hill City Café. Fat Chick was tired because she hadn’t slept well for a few days, and she was salivating over the potatoes, sausages, and bacon. Skinny quickly ordered what had lately become my usual breakfast: two eggs over easy, with wheat toast and sliced tomatoes. I imagined the tomatoes as potatoes, cut up and fried with onions and enough butter to make them crispy and tender.

When I got to the cash, Chick stared at the biggest cinnamon rolls she’d ever seen; they were as wide as a cantaloupe and as high as a short mug of coffee. Some had white icing, and others had melted sugar. I leaned into the counter. They smelled deliciously of bread, yeast, caramel, sugar, butter, and spice. She wanted to roll in them, to lather her breasts and belly in icing and soft yummy bits of dough. I yanked her out the door.

Inanna Admin –

Horses in the Sand: A Memoir by Lorrie Potvin

reviewed by Cheryl Sutherland

Frontenac News – June 1, 2022

https://www.frontenacnews.ca/item/15685-horses-in-the-sand-by-lorrie-potvin

Lorrie Potvin’s Horses in the Sand is a compelling and powerful memoir exploring the concepts of identity and finding home. Set primarily in eastern Ontario and the Ottawa Valley, Potvin’s writing chronicles her experiences of childhood familial dysfunction and her path to self-reclamation.

Caught in a narrative of abuse and violence from childhood, Lorrie spends decades searching for the pieces of her identity that were stolen. How do you make sense of who you are when you have been told that you were “bad and ugly” from a very young age? How do you reconcile the way you feel with the ways in which the outside world tells you that you should feel?

How do you move beyond not simply accepting who you think you may be and make your way to celebrating the uniqueness of who you truly are?

Resilient from childhood, Lorrie’s grit, determination, insight and steadfast questioning of the stereotypes and assumptions that embodied her younger years and threatened to contain her, laid the groundwork from which she would launch herself into adulthood. Horses in the Sand captures both the innocence of childhood and the fractures that occur when one’s early years are punctuated by violence and maternal disengagement.

Growing up in the 1970s-80s with a non-conforming sexual identity, Potvin challenges gender roles and becomes certified in a traditionally male dominated field. She follows her heart, when many others would have chosen to take an easier route. Her identity as a tradeswoman and ultimately a teacher in the field, is not only impressive, but profoundly heartwarming. You cannot help as a reader to wish you had been able to cheer her on in person while she fought against the confines of her gender imposed societal limitations.

The discovery of her previously unknown Metis identity and the ways in which she includes the reader in her journey to self understanding and celebration is such an honour to witness. Taking the time to fully explore and understand how her indigenous identity plays such a tremendous role in helping her find her way home. Horses in the Sand provides the reader not only with a unique lens in which to understand the concept of self-reclamation; it also allows you to recognize the varied and complex ways in which our identities and beliefs about what those identities mean affects the very way in which we understand and navigate our lives.

Growing up with a queer identity in 70s and 80s Eastern Ontario was to experience oppression, alienation, discrimination and shame. How any of us made it through continues to amaze me. I cannot help but wonder what our lives would have been like if who we are was something to be celebrated instead of hidden behind those rickety closet doors. At the time when Lorrie and I were growing up very few people ever spoke the words lesbian or gay, let alone anything else. And when they did those words were flung around as insults to demean and make small those who did not fit the mold that society had fabricated.

Horses in the Sand is a timely celebration of both sexual and indigenous identity(ies). It is a brutally honest and courageous account of one woman’s struggle, but it reaches far beyond the individual experience.

Lorrie Potion’s memoir is a story that can give people hope, especially to those struggling with their sexual and indigenous identities.

Inanna Admin –

All My Relations: Reflections on Horses in the Sand

Horses in the Sand: A Memoir by Lorrie Potvin

reviewed by Rena Upitis

The Humm – June 2022

https://thehumm.com/online/article.cfm?articleid=3168

One might wonder why Lorrie Potvin invited me to review her utterly compelling memoir, Horses in the Sand. On the surface we have little in common. I’m a tried-and-true scholarly sort, not a single tattoo on my body, and a straight-up cisgendered heterosexual white woman. I am keenly aware that I have lived a life of extraordinary privilege.

Lorrie avoids wearing skirts because wearing them once made her fearful and identified her as female, which singled her out as “prey.” One of my favourite pre-pandemic pastimes involved driving to New York City, dressing up in a velvet gown, and attending an opera at the Met for a full-on evening of over-the-top Puccini arias. Unlike Lorrie, I have never owned a Harley, nor have I have ever wondered about the identify of my birth father. I don’t battle a chronic illness. I couldn’t imagine forging a career as a welder — my few nearly fatal brushes with a welding torch only reinforce my respect for Lorrie’s skills.

But carpentry I get. Next to the velvet dresses in my closet are my work clothes. In the opening of the book, Lorrie writes:

“It was the summer of 2019 when I drove in the last screw holding the bottom stair rail to its post. The rata-tat-tat of the drill echoed sharply through the acreage of trees and across the mirror-like surface of the lake. It only took a few seconds for the drill to stall, satisfied with the set of the Robertson screw… I sighed heavily when I stood, the moan coming from finishing the porch stairs as much as it did from the pain of my back and knees trying to right themselves.”

I can picture the scene. I expect readers who have built their own homes, sheds, or workshops will feel the same. Indeed, Lorrie and I have built many things together at Wintergreen Studios, an educational retreat centre a mere 20 minutes from where she lives. We talk tools. We share tools. And we solve problems that invariably arise when building or renovating – problems as gnarly as the most complex geometric theorems. As a small woman in her early 60s, I can picture just about everything Lorrie writes about the building process, although in her case, the physical limitations come from living with MS. She tells the story of having several big pieces of glass to move, about starting with the lightest one to build confidence, moving to a heavier one next. That strategy (I know it well) is illustrative of the deliberate planning and choice-making in this kind of creative work.

I get teaching, too. I taught for decades at the Faculty of Education at Queen’s University where Lorrie received her teaching credentials to become a secondary school shop teacher. And make no mistake, Lorrie is a gifted teacher. I have learned much from her (and not just about carpentry). But her subject and appearance raised eyebrows in the school system. Asked by a student if she was a real teacher, she writes:

“When I said that I was, she looked confused and said in a voice only teenage girls who know they’re always right can muster, “Teachers don’t wear jeans and black leather biker jackets, you know.” It wouldn’t be the last time someone asked me this question. It usually came from girls who were unable to reconcile my look with what they thought a “girl teacher” should look like. I wore men’s clothes and had my hair cut short, and a couple of my tattoos were visible when I wore short sleeves. The art made some kids gasp and point…The older boys would say, “Nice ink.””

Lorrie tells many stories about her teaching days, and those of us who have spent time in the classroom will recognize her as one of the teachers we would wish for our own children.

There is, in this book, much darkness. The little girl who took a stick and drew horses in the sand on a gravel road was lost for many years to violence, addiction, and psychological cruelty. In her childhood years, she and her brothers were taught to “keep secrets, lie, cheat, steal, yell, scream, and beat each other up … to meet every demand, conflict, difficulty, indecision, uncertainty, and fear with anger… it was raging anger built on a bedrock of resentments. It was how we lived, and we knew it as normal.”

Her early work as a tradeswoman only continued the injustices and cruelty where “sexual harassment, bullying, abuse, lower pay, and paternalistic and hierarchical structures” were the order of the day. Lorrie’s desire to live a better life was seeded from a life with much darkness, coupled with those impulses to make art in the gravel.

Even before Lorrie discovered her Indigenous ancestry (and believe me, that’s a story that you will want to read for yourself), she had great reverence for the natural world. When she began the decades long process of building her home, she mused about what it is like to build in the bush, about how she learned that “when you build in the bush, the temperamental forces of Mother Earth—the wind, water, and fire, along with her plant and animal nations—immediately start taking over. Some would say they were claiming rightful ownership … by resisting our intrusion.” Here is another place where our worlds intersect. There are many small cabins in the woods at Wintergreen, and non-human guests are a constant. After railing against the unwanted inhabitants, I finally came to understand that there would always be ants and phoebes, deer mice and grey rat snakes living in the crevices, and moreover, that they had every right to be there. There is an Indigenous expression, “all my relations,” that captures this notion. Lorrie writes:

“When I [say] all my relations, I [am] talking about our relations with self, family, friends, and people. But I [am] also talking about being in kinship with the world we live in: the four-leggeds, the swimmers, the fliers, the crawlers, Mother Earth, the water, Father Sky, the tall standing ones, the plant world, the stars, the energies of Grandmother Moon and Grandfather Sun, the wind, the thunderers, the rain, the snow, and all the great mysteries lived and yet to be lived. Nothing is lesser than the other and each are vital to the whole. That is all our relations.”

You will read about how Lorrie’s immersion into Indigenous sharing circles and ceremonies led her back to that young child who drew horses in the sand, how sharing circles and ceremonies were places where she felt accepted and started to heal her “feminine spirit.” She explains that “it was important to recognize my femininity, which I had denied for most of my life, so I could heal the little girl that had been abused and cast aside. At the same time, it was essential I recognized how strongly I carried the masculine spirit and acknowledge the shame and harm I’d done to myself in trying to hide my true nature.”

Because Lorrie’s writing about teaching and about building the house that she and Paula now call home rings so true, it makes me trust the rest – the stories about worlds that are not mine. This is what makes the work so powerful. It is not just evocative writing, full of beauty and metaphor: it is authentic writing. The details in the particulars illuminate a path which, if we follow, we just might learn to live with all our relations. I am convinced that if we are ever going to mitigate the climate crisis and heal the deep and growing divides in our country, we will only do so when we come together as a truly inclusive community. How to do that? By listening, by forming friendships, by reaching out to those who, on the surface, may not seem to have much in common with us. That is the gift of Horses in the Sand. Read it. Learn about Lorrie and her struggles and triumphs, and in the process, learn more about who you are, and what we must all do to thrive in the tender years to come. With all our relations.

Inanna Admin –

The Minerva Reader – June 27, 2022

https://theminervareader.com/library-2022

I loved First Gear: A Motorcycle Memoir so much and this sequel more than fulfilled my expectations. Lorrie Potvin pulls you into the story with compelling immediacy and you can’t put the book down. The story is inspiring and the peripheral characters are vivid, and even if they flit through the narrative, their presence is strong and poignant. A powerful, memorable read for all the best reasons.