In this Inanna author blog we follow poet Ilona Martonfi, who was born in Budapest, and now resides in Montreal, who, decades after she lived in a war refugee camp in Austria went back to construct her memorials. A sgraffito excavation, scraping through layers of history in a search for stories of the disappeared.

Fragmented, vivid, without resolution. Her child self watches, she goes and has lunch. It’s puliszka, maize porridge, her mother cooked. The bombed houses. Playing in the rubble.

The Lost and Unlost

“Not only the poets “pass through” their experiences but also their very languages, which continue to “bear wounds, legible in the line breaks, in constellations of imagery, in ruptures of utterance, in silences and fissures of written speech.”– Carolyn Forché www.poetryfoundation.org › Poetry Magazine

Offering a witness poem “Terezín” forthcoming in The Tempest (Inanna Publications, 2022), also published in the chapbook Moth (Cactus Press, 2020). Appeared in Montréal Serai.

Terezin

Oil and ink, gesso on unstretched canvas. Write. Write it. A search for the disappeared.

A group here, and another there. Memories trapped in erasure. We are not safe, says one character. Scraping, scratching away with palette knife. Grey ink running with the black ink. Write: the painted people call to us. Shadow us. Possess us. I put down abstract marks. Look at my ancestors. Concerts in cellars and attics. Percussion, a cello, double bass. Lilac hills of Prague.

Windowless cattle wagons. Ghetto Terezin filled with bumblebees.

Such, such blue sky. On a small stage, within a stage. Not rifles. Not screams. Land of stipa grasses. Marsh gladiolus. Tracing in figures. Until the lost fathers and mothers, brothers, and sisters, stand upon this wooden easel. Write: children’s fairy tale opera Brundibár. Kocour, the Cat. A dog and a sparrow.

(File: A drawing of children of Ghetto Białystok transported to Terezín in August 1943 by Otto Ungar.jpg Wikimedia)

“Brundibár is a children’s opera by Jewish Czech composer Hans Krása with a libretto by Adolf Hoffmeister, made most famous by performances by the children of Theresienstadt concentration camp (Terezín) in occupied Czechoslovakia. The name comes from a Czech colloquialism for a bumblebee.” —Wikipedia

Children’s Opera Flašinetář Brundibár (Organ-grinder Brundibár)

“The story of Brundibár is a simple tale of good and evil. Aninka and Pepiček, two little children, have a sick mother who needs milk to get better according to the doctor’s prescription. The children visit the town marketplace where three sellers (an ice-cream man, a baker and a milkman) hawk their goods, but they do not have money to buy milk. Seeing the organ-grinder, called Brundibár, playing on the street corner, they decide to imitate him and raise money by singing, too. When they do so, their voices are too soft to be heard alongside his and annoy Brundibár who chases them away together with a policeman. During the night, which the children spend on a bench, three animals – a dog, a cat and a sparrow – come to their aid and advise them to set up a chorus together with other children. In the morning, children from the neighbourhood join them in forming a chorus. They sing a beautiful lullaby, which moves the townspeople; then Aninka and Pepíček are rewarded with donations from the passers-by. In an unguarded moment, Brundibár sneaks in and steals their money. After a brief chase by the children and the animals, Brundibár is caught and the money is recovered. The opera concludes with all the children singing together a song of victory over the evil organ-grinder.” www.tandfonline.com › doi › full

A Poet by any Other Name

“The word poet, which has been in use in English for more than 600 years, comes from the Greek word poiētēs, itself from poiein, meaning “to make.” The word also shares an ancestor with the Sanskrit word cinoti, meaning “he gathers, heaps up.” —Merriam-Webster

Where Art has Bleached Away Colour:

I write a haiku sequence: Haiku a Japanese poem of seventeen syllables, in three lines of five, seven, and five.

Sgraffito

oil pastel sgraffito

of his own mortality

in its stark white frame

frenzied mark making

and the depth of tone in the

absence of colour

layers of grey paint

yet he sees faces clutching

this cotton canvas

Sgraffito definition:

“The word sgraffito comes from the Italian language and is derived from graffiare “to scratch”, ultimately from the Greek γράφειν gráphein, “to write”. One use of sgraffito is seen in its simplified painting technique creating work through surface distortion. One coat of paint is left to dry on a canvas. Another coat of a different colour is painted on top of the first layer. The artist then uses a palette knife to scratch out a design, leaving behind an image in the colour of the first coat of paint. This can also be achieved by using oil pastels for the first layer and black ink for the top layer.” —Wikipedia

Lost Voices

In my research and note taking I came across the method of working sgraffito by Ricky Romain, a UK Human Rights artist: “I created panels as a base for a sgraffito (scratching) technique to scrape through layers of paint,” he said. “This method is a kind of excavation, a search for imagery that emerges by digging into the subconscious to discover representations of who I imagine to be ‘the disappeared’. This process could be described as ‘archaeological’ and it in some way mirrors the action of relatives digging for the remains of loved ones who have been taken with no explanation.” www.rickyromain.com › uploads › 2015/04 › Marking…

Babi Yar Symphony No. 13: Art Destroys Silence

“Dmitri Shostakovich, composing his Babi Yar Symphony No. 13, based on Yevtushenko’s poem commemorating the murder of the Jews of Kiev, comments, People knew about Babi Yar before Yevtushenko’s poem, but they were silent. Art destroys silence.” —Wikipedia

(File:Babi Jar ravijn.jpg Wikimedia Mark Voorendt)

Free Verse and Split Lines definition:

“Irregular line breaks give a poem more of a sing-song rhythm that is best appreciated by reading it aloud. Split lines of poetry may also emphasize the concluding thoughts. If the reader reads the poem aloud, the emphases on the second parts of lines becomes clearer.” www.encyclopedia.com › arts › educational-magazines

How Did You First Engage With Poetry?

The first mention of poetry in my diary had been in the 70s, when I quoted from “Babi Yar” by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, which I had read in a magazine.

And he was more than a poet – he was a citizen taking a stand. Searching for a tombstone, a historical marker, but finding nothing. It took him two hours to write the lament about the destruction caused by anti-Semitism. The poem that begins:

No monument stands over Babi Yar.

A drop sheer as a crude gravestone.

I am afraid.

Today I am as old in years

as all the Jewish people.

Now I seem to be

a Jew.

“Babi Yar, where even the grass cannot rest at the site of so much slaughter. Even the physical location has become representative of the massacre that occurred there. The trees remain as witnesses to the events of 1941, standing as if they judge those who committed this atrocity. The trees also judge those who allowed it to happen and those who have forgotten to honour this massacre. All of nature silently cries out in protest, according to the speaker, who joins in the silent cries of the hundred thousand who died at Babi Yar.” www.encyclopedia.com › arts › educational-magazines

I write a haiku sequence “Babi Yar, 2” for Section I of The Tempest. Also appears in Moth.

little white bones

people walking on ashes

a hillock of weeds

Meeting my Sixth Chapbook Moth

Offering free verse, ekphrastic poems, prose poems, haiku and haibun, often staccato in rhythm and spare in style. The poems in Moth come together as elegiac meditations, drawing on history, and on mythology. Witness-bearing poetry. Exile from place. The dispossessed.

Advance Praise for Moth

“In Moth, Ilona Martonfi weaves dreams with reality. In this space “where the wind howls / thorn grows wild in the gorge / the colour of roses” and readers glimpse memories that “have left the moon unlit.”

—Blossom Thom’s poems document Black experiences while playing with form. Poetry has appeared in Montréal Serai, Kola, and elsewhere

“The poetry of Ilona Martonfi beautifully intertwines emotionally disturbing political realities with true meek living experiences. She conveys her deep engagement with world justice and peace with subtle poignant lyrical images leaving the reader to walk breathlessly through the pain and sorrows of history.”

—Gloria Macher is an award winning Latin American writer. Has published five novels and a collection of short stories

A climate change poem “Totenwald” from Moth. Also published in Montréal Serai.

Totenwald

I will go now, learn the language of the

woods, and go to the huts, where the flautists

are practicing, the sky violet. I will

learn the trees. Gneiss hillocks of mosses.

I shall weave and knot jute ropes around grey

bark and branches. Lime-green wings and

furry white body. Obits for those whose cairns are

missing, those who are numbers. Pupa of the

Luna moth eclosing, I will journey through

the Totenwald, a boggy, stygian fen.

Blueberries and wild roses standing in the sphagnum,

knots and ropes, using ropes as lines, an ode I use

to knot each piece, cocoon wrapped in leaves as home.

I will go now where river birch grows. Hold a

wake among rhodora, red osier dogwood withy.

I hear a small blackwater stream

quarrelling with metaphor.

Wetness the shape of water on skin.

The bodies we speak of inhabiting.

Papery white moonflowers. A bittern calls.

A Digital Book Launch in the Time of COVID 19 !

I wish to thank Rue Towers Writers for their support and friendship. Thanks to talented Cover Designer Bianca Cuffaro. A special thank you to Devon Gallant, Cactus Press Publisher, for bringing this chapbook into publication. Moth is available to read now for free on the Cactus Press website. https://www.cactuspresspoetry.com/

Prose Poetry definition:

“Prose poetry is poetry written in prose form instead of verse form, while preserving poetic qualities such as heightened imagery, parataxis, and emotional effects. However, it makes use of poetic devices such as fragmentation, compression, repetition, rhyme, metaphor, and figures of speech.” —Wikipedia

I conclude with a prose poem “Summernote V” from Moth, forthcoming in The Tempest. Also appeared in Montréal Serai. And I wish to express gratitude to the fantastic Inanna Author blog team for posting my blog.

Summernote V

Call her goddess of heath and yellow gorse. Tell her you have left the moon unlit. Snuggled into its folds. Swamp-fed forest creeks. Grafted to fen carr, sedge grasses. Dwarf blackberries. See if she believes you. You can neglect wood bluebells, red-purple milkweed, these rimes, flowerings begging for time. Paper birch trees that chafe refrains, disjunctions, oxygen for photosynthesis. Tell her it’s the Earth here. Tell her escape won’t work, this far into the scrub habitat. How over there in flattened boxes sit clawed wheat fields knotted in dirt. Cherry trees. Plum. Stripping away punctuation. Tell her that you are out here all alone. Tell her. You have summoned the wind. Swallows flying low. Smell of petrichor after rain falls. The blood of the stone. See if she believes you.

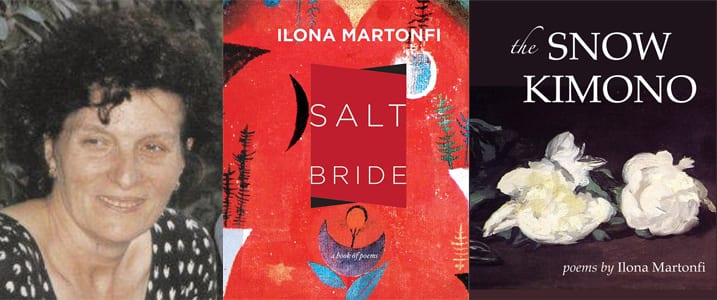

Ilona Martonfi is an editor, poet, curator and activist, author of four poetry books, her most recent title is Salt Bride (Inanna, 2019). Forthcoming, The Tempest (Inanna, 2022). Writes in six chapbooks, numerous journals across Canada and abroad. Recently, her poem “Dachau Visit on a Rainy Day” was nominated for the 2018 Pushcart Prize. She is the founder and curator of Visual Arts Centre Reading Series, and Argo Bookshop Reading Series. She is also the recipient of the Quebec Writers’ Federation 2010 Community Award.