Women talk! In many cultures across the world women nurture, take care of us at all stages of life and when they do, they connect with their charges or lighten their load by talking and singing. My day to day conversations these days are most often with the women who come every day to provide personal care for my mum, now 89 years old. I’ve moved back to my hometown, Manchester England, to be a companion for my mother as she ages. Led by one of Manchester’s own, Emmeline Pankhurst, feminism brought change into the lives of women in much of the Western world. Still, improvements in education of women and the movement of more women into “the professions” hasn’t changed much in the lives of working class women in the suburbs of Manchester. Many leave school at 16 and take up jobs in their community, perhaps shop assistants or servers and increasingly as personal care attendants. The aging population grows and such jobs are available with only minimal training. The women taking these jobs are rewarded with zero-hours contracts and low wages and many of them move into marriage and then look after their own families. Housework (as it has always been known) has, of course, low or no monetary reward or societal acknowledgement that the work is essential to the economic development of the country. The carers only rarely sing (and when they do it’s because Mum prompts it with one of her favourite tunes) but they natter away as they move through their tasks to keep Mum clean, healthy and happy. Yes, “natter” which brings me to dialect.¹ Natter, meaning to talk freely and in an upbeat and lively manner, perhaps to gossip. I eavesdrop on the carers conversations with my mother or natter back myself.

“Ooh, it’s dead cold out there. Mind you, I’m dead mard me”. (Dead = very; mard = weak of character; me = the reflexive pronoun is added to the end of sentences telling about the self).

“Are you ‘avin’ some dinner?” (Dropping ‘h’ and final ng, features of Manchester accent; Dinner is the midday meal).

“Ee-y’are, let me do that for you”. (“Ee-y-are”, Here you are, is a type of excuse me, an interruption in thought).

“What it is, right, is that…”. (A general introduction to an explanation).

“Eh-up, while I’ve moved this chair” (“Eh-up” is a general warning, maybe “watch out” or just an attention getter; “while” means until rather than during.)

Eh-up…..

“I ‘ad to cadge a lift to work this mornin’.” (“cadge” = scrounge or beg).

“I can’t be mithered with it all”. (“mithered” = bothered).

“Mind yerself! That water’s ‘ot” (“Mind yerself” = Look out! That water’s hot)

After living thirty-nine years in British Columbia, Canada I’m back to the joys of listening to language as she is spoken in the north of England. I’m delighted to hear, and use again, more strongly, my own local accent and dialect. So much about language is woven, a tight warp and weft, in British culture. The way we speak tells so much more about us than the words we say. Your accent and the dialect you speak immediately lets your listener know where you are from. And not just in a broad way, your county or region but city, town or village can often be identified in your expressions and in how you form your vowels and consonants. And that’s just the English speakers.

There are as many as 200 languages other than English spoken in Manchester including Urdu, Arabic, Chinese and Polish. I’d fully expected much to have changed over the years I’ve been away. And, indeed, Manchester’s population has grown steadily, building on the arrival of the first immigrants in the 19th century. Its population hit a 19 per cent increase in the first decade of the new millennium. There’s also no question that globalisation and the influx of all things American into our high streets, television, social media have brought huge changes to the way the British eat, socialise, find entertainment and talk, but the “old ways” and the “old words” are still present and strong. Where I live in the south part of Greater Manchester, burgers haven’t yet completely replaced fish, chips and mushy peas, you’ll find a good conversation in your local pub (though it’s likely been updated and will sell fancy menu items way beyond pies, pickled eggs and packets of crisps). Though people watch movies on Netflix you can still go to see a picture at the cinema and, daily, you’ll be greeted with “’I-ya! (Hi!) A’ y’all-right?” (how are you?) to which you might reply “Yeah, I’m doin’ aw-right, ta”. (I’m fine, thanks). And when I travel on the bus or go shopping at the nearby Civic Centre, I hear a diversity of sound in the voices of my community.

The buses, especially the local services travelling between the small communities that, together make up the suburbs and rural areas adjacent to the “big city”, are lively places where folks pass the time of day and share their own news or whatever is going down in their community. Friends meet by chance on their way to do the shopping or attend doctor’s appointments.

“A’-yer-‘right?” ( How are you?)

“Not bad. A’ve ‘ad me eyes done. Eh, they’re sound them at the eye ‘ospital.” (I’ve had my eyes done. “they’re sound them” = they’re very good/very skilled + the reflexive pronoun as noted above)

“Oh, yeah, what did yer ‘ave done?” (what did you have done?)

Eh-up…

“Cataracts. Last week. I’m chuffed with ‘ow they are. I can see dead clear”. (chuffed = pleased; dead = very.)

***

“Eh, look it’s started spittin’. A’ll be glad to be ‘ome for a brew!” (spittin’ = raining lightly, drizzling; ‘ome for a brew = home for a cup of tea.)

“I only ‘ave to walk a bit and then down ginnel” (ginnel = a narrow path between buildings like an alley)

“ ‘ow’s your kid? Still supportin’ City? ‘e’ll see sense one o’ these days!” (‘ow’s your kid = How’s your son/daughter; “City” = Manchester City, football i.e. soccer team; ‘e’ll see sense = he’ll come to his senses, implying he’s supporting the wrong team.)

“They’ve done well last couple o’ matches!”

“Oh, aye, a right turn up fo’ the book, that! Yer never know yer luck in a raffle, eh?” (a right turn up fo’ the book = a surprise – usually positive; yer luck in a raffle = a common expression, you never know your luck).

****

When I consider the multi-hues of language in Manchester, I like to think of two aspects. The “big L” sort – “Language” and then “small l” – “language”. The first is like an enormous bunch of flowers, many different kinds all tied up in a beautiful, colourful bouquet (English, Polish, French, Urdu, Arabic, Russian, Chinese). Then, there’s the small, like all the individual petals, sepals, leaves, all the parts of each separate flower. In terms of early language learning, these are the parts of each specific language that children learn: words, sentences, prosody and the hows and whens of being a communicator. Accent and dialect belong here too. The Multilingual Manchester project², led by Professor Yaron Matras at Manchester Metropolitan University, reports that of the 480,000 people who live in Greater Manchester, half are multilingual. The report adds: “In 2012, 3000 pupils at Manchester state schools sat GCSE exams in foreign languages whilst the city’s libraries offer 20,000 books and other media in languages other than English.” When Mancunian accent and dialect are laid atop a language other than English, my brain gets giddy and I’m excited by this magic of possibilities in verbal expression!

And that last sentence introduces another English language revelation: the demonyms of British place names. Mancunian describes a person from Manchester or anything which belongs to the city. In

Eh-up…

typical, playful British fashion, it is shortened to Manc. We are Manc and Proud! If you’re interested in looking further afield for other interesting demonyms in Britain, you’ll also find (just sticking to the North): Liverpudlian (Liverpool), Leodensian (Leeds), Geordie (Northumbria) and more.

Everyday discourse glints with turns of phrase, word usage nothing short of poetic. I love the conversations I get into every single day! The words I hear take me back to my childhood, remind me of my Nana, my Great Granny, long since passed on and aunts and uncles some of whom are still around to tell me their tales from years past or just to give me their latest in their strong Manc voices.

¹ A Google search of “Manchester dialect” brings up plenty of lists of words and expressions.

² See Manchester Multilingual Project at http://mlm.humanities.manchester.ac.uk/

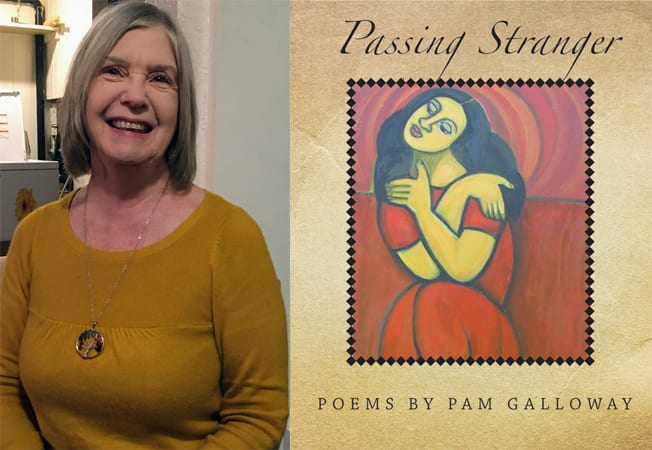

—Pam Galloway, author of Passing Stranger

Ey up, that’s reight gradely our Pam

or

That’s a very good article Pamela

I hope we never lose our regional dialects.

Very interesting article Pam. I forget how much of my own day to day speech is dialectic, though having been nomadic in my earlier years I have picked up words from other dialects and languages. I often use “reet” a corruption of “right” which originates in Yorkshire. Unsurprising, given as a child I would often spend holidays with my favourite sister, who lived in Leeds.

I’m so taken with this description of the ‘magic of possibilities’ of language that Manchester brings to Galloway’s lively attention. I used to delight in eavesdropping while traveling or, before the pandemic, in restaurants or on buses, on fascinating accents and non-English words. (My Maritime relatives used to refer to these voices/people as those who come from ‘away,’ as if their own part of the world was the its centre.) This article, so well done, reminds me of something the great short story writer, Flannery O’Connor, used to say about the impoverishment of literature as television eliminated the local accents and dialects of characters, but it’s clear in Manchester this has only been enhanced by immigration and the steady embrace of Mancunians around their natural sound. Good news!

Thanks for your astute perceptions Leslie.

Oh, Pam, this is such a rich piece! As someone who’s almost always lived in North America, I learned a lot. And perhaps my favourite detail is the fact that when you say ‘I’m back to the joys of listening to language as she is spoken in the north of England’ language is feminine. Vive la langue!