In this second installment of a three-part blog series on Helen Weinzweig, Rhoda Rabinowitz Green writes about traumatic experiences of Helen’s childhood, her growing awareness of thwarted self-fullfilment and her search for identity, and how they are revealed in her writing.

I. “What Would Helen Say?” (Inanna, January 6, 2016)

I. “What Would Helen Say?” (Inanna, January 6, 2016)

II.”From Pain to Prose’” (Inanna, March 23, 2016)

Helen Weinzweig is the author of the novels Passing Ceremony and Basic Black with Pearls, winner of the Toronto Book Award. Her short story collection, A View from the Roof, was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction. Helen Weinzweig died in Toronto in 2010.

My interest in Helen Weinzweig and her work was renewed with the recent republication of her second novel, Basic Black with Pearls (Anansi). Trying to remember what Helen had said about writing back in the early 1990s when she’d agreed to mentor me, coupled with the desire to satisfy my curiosity, led me to search through my file notes, where I came across invaluable words of advice she’d offered. What I found in those notes impelled me to write “What Would Helen Say?” posted in January 2016 on Inanna’s Blog. I found in researching the piece that there was so much to her life and work I couldn’t possibly include it all in one posting and determined to follow it up with another, expanding on the first.

Not surprisingly, after writing several drafts of “From Pain to Prose,” I again determined there was too much material to be absorbed in one reading. This segment, then, will speak to the traumatic experiences of her childhood, her growing awareness of thwarted self-fulfilment and her search for identity, and how they are revealed in her writing. Because of the close relationship between her life experiences and the style she chose to best express them, the sequel to this blog entry will deal with how she used magic realism to that end.

Given what we know of her life, career and personal relationships, we can’t help but read an autobiographical truth into Helen’s novels and stories. Nor can we help but recognize the pain that imbues both her fiction and her life.

One of the most telling and intimate portraits of Helen can be found in Michael Posner’s Globe & Mail 2010 Obit: “Helen Weinzweig Turned Personal Pain into Beautiful Prose.” [The article contains quotes from an interview with Posner based on my personal/professional relationship with her.] As well, poet Ruth Panofsky, in a very full account, further tells of Weinzweig’s struggles through childhood, adolescence, and adulthood as student, wife, mother and eventually, writer (Panofsky, “Sense of Loss; A Profile,” The Atlantis, Vol. 22.1). More can be found in Stacey May Fowles’ “Special to the Globe and Mail,” 2015.

Helen grew up in the impoverished polish ghetto of Radom, Poland under constant threat of pogroms. She was the only child of a “tempestuous” marriage between the “. . . young, illiterate, fiercely independent [and] physically beautiful” Lily Wekselman and her father, the “brilliant Talmudic scholar turned atheist and anarchist,” Joseph Tennenbaum. The marriage didn’t survive. Helen arrived in Canada (with her then-divorced mother), aged 9 and illiterate. She never understood why she hadn’t learned to read or write but conjectured that after being expelled for stealing a book she never returned to school. Was that because of shame or because her mother couldn’t afford to (or wouldn’t) buy the schoolbooks? She didn’t know. (Posner)

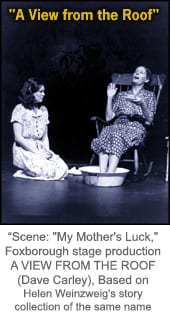

Weinzweig grew up in Toronto’s Jewish immigrant district, now the gentrified “Annex.” Her life-long obsession to escape the “tyranny of poverty” and “working-class oppression” (Panofsky) provides the backstory for a long monologue, “My Mother’s Luck,” (A View from the Roof), acknowledged as autobiographical. Helen’s mother earned a scant living in Toronto as a hairdresser and “welcomed a parade of unsuitable men into their lives, some [three] as husbands, others as transient lovers,” resulting in a number of abortions. (Posner) Because of being shut out of the house while her mother “entertained,” Helen wandered the neighbourhood, house-to-house, street-to-street, the brunt of ostracism because of her mother’s life style. Yet, in “My Mother’s Luck,” she sympathetically explains her emotionally abusive mother’s behaviour as stemming from the need to be sole provider for Helen, Helen’s sisters and grandfather, at a time when such a role was not normally required of women. Fortunately, she found refuge at the St. George’s Children’s Library. There, librarian Sadie Bush nurtured her with treats of biscuits and books, instilling in Helen a love of reading and language. (Posner) The theme of poverty runs through the whole of her work.

Weinzweig grew up in Toronto’s Jewish immigrant district, now the gentrified “Annex.” Her life-long obsession to escape the “tyranny of poverty” and “working-class oppression” (Panofsky) provides the backstory for a long monologue, “My Mother’s Luck,” (A View from the Roof), acknowledged as autobiographical. Helen’s mother earned a scant living in Toronto as a hairdresser and “welcomed a parade of unsuitable men into their lives, some [three] as husbands, others as transient lovers,” resulting in a number of abortions. (Posner) Because of being shut out of the house while her mother “entertained,” Helen wandered the neighbourhood, house-to-house, street-to-street, the brunt of ostracism because of her mother’s life style. Yet, in “My Mother’s Luck,” she sympathetically explains her emotionally abusive mother’s behaviour as stemming from the need to be sole provider for Helen, Helen’s sisters and grandfather, at a time when such a role was not normally required of women. Fortunately, she found refuge at the St. George’s Children’s Library. There, librarian Sadie Bush nurtured her with treats of biscuits and books, instilling in Helen a love of reading and language. (Posner) The theme of poverty runs through the whole of her work.

Later in life, her difficult adolescence became grist for her writing mill. At 17, thinking to have a reunion with her long-estranged father in Milan, she found herself essentially a captive for months, “kidnapped” by a father who refused to allow her to leave. On returning to Toronto, she contracted tuberculosis. During the next two years in Gravenhurst, a sanatorium for the treatment of tuberculosis, and motivated by a keen intellectual curiosity, she educated herself in world religion and Western literature. (Posner) She soon came to the realization that all the books she was reading were male authored —written from the male perspective. It was the male “voice’ she was hearing; the women’s voice was silent; unacknowledged. “One of the things I had to learn . . . was, what do I as a woman feel like,” she has said. “All the literary forms . . . all the philosophies were men’s . . . The hardest part . . . was learning to use the first person singular. It was then that I was shocked into admitting that I rarely said “I” except in apology . . .” (Weinzweig, “The Interrupted Sex,” quoted in Panofsky and Fowles)

Forced by the economic consequences of the Depression, she left high school at the end of her junior year at Harbord Collegiate. A chance meeting on the street of high school friend, John Weinzweig, led eventually to their marriage. Her son, Paul, has been quoted as saying: “The only immediate problem was that [my mother] came from the wrong side of the streetcar tracks. She had an uphill battle to convince the Jewish bourgeoisie that she was legit.” (Posner) Explaining her decision to marry, she said: “I grew up without a sense of family . . . I tried to create a family life out of my head. I feel I failed. I still don’t know . . . what makes a family. So the ‘sense’ of family creeps into my work in a negative way . . . My mother] refused to follow the path of other women . . . [So] I decided I would be respectable, and became more so than Caesar’s wife. (Jenoff, “Helen Weinzweig: “Her Life and Work. An Interview,” Waves 1985; quoted in Panofsky).

Speaking about her novel Basic Black with Pearls, Helen said: “[The novel] reflects my desire to belong to [a] bourgeois, nuclear family. The inherent conflict was to want it and to despise it.” (Panofsky, ‘At Odds in the World,” Essays on Jewish Canadian Women Writers, Ryerson, 2008; quoted in Posner). She devoted herself until age 45 to being a homemaker and mother, volunteering, as many women do while raising their children. Helen was quoted in 1976, after publication of her first novel, Passing Ceremony (1973), as saying, “Both John and I lived for his career [italics mine].” (Keeler, National Post, Basic Black with Pearls Review; 2015). In my own catalogue of memories of conversations with Helen Weinzweig, one revelation, delivered with poignant dismay, has never left me: “John never reads my work.”

There has been much written on the success and fame of her composer husband John Weinzweig. It is John who is referred to as “revered, who wrote compositions for film, radio, theatre, orchestra, chamber groups, solo instruments, choruses. John, professor at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music, Officer of the Order of Canada. He who is presented with awards and testimonials; who establishes (with others) the Canadian League of Composers and writes extensively on music and composing. His bio is extensive, his output prolific.

As for Helen, she published two novels and a number of stories: Basic Black with Pearls won the City of Toronto Book Award; A View from the Roof, a collection of 13, was nominated for the Governor General’s Award. Passing Ceremony broke new ground in Canada as a highly experimental work in the best tradition of avant-garde writers. She was a founding member of the Writers’ Union of Canada, held positions as Playwright and as Writer-in-Residence at Tarragon Theatre and University of New Brunswick, respectively. In her approach to reaching a final draft, she was meticulous, constantly rewriting. That, along with the fact of having begun to write relatively late in life, led Anansi’s Editor James Polk to comment: “A painstaking artist, she . . . produced relatively little. But what there was, was choice.” (quoted in Posner)

But it was John who was highly prolific, held positions in many high profile capacities and was extensively written about. In short, it was John who was famous.

With her two sons growing up and away, and her husband engrossed in himself and his career, she met with a Toronto psychologist Margaret McQuaid. Helen was in her mid-forties. One day the psychologist suggested to Helen that she put her thoughts and feelings to paper in just the way she’d been describing them. Helen took her up on it and so began her exploration of the many unresolved issues from her traumatic childhood and adolescence, as well as her role as a woman in a male dominant society and marriage. Helen says the writing gave her renewed life.

It wasn’t until her sixties that she began writing Basic Black with Pearls, at a time when she was seeking “a female-gendered narrative form that would articulate the feelings of depersonalization and fragmentation that women, particularly of her generation, experience.” (Panofsky) The book’s protagonist Shirley’s narrative becomes a personal transference of Helen’s deeply felt pain arising out of her own experience, that of prevailing personal and societal male control, determining her destiny and options, placing limits on her potential. (Fowles, Globe and Mail, August 2015).

On first bringing my own work to Helen, seeking her critical insights, Helen observed: “All the stuff — the substance — necessary for good writing is already here in your manuscripts, but something is keeping them from getting published.” She then proceeded to work with me on finding the form and style to best support and reveal each story’s emotional meaning. For Helen, it was magic realism that provided the means for expressing that which would otherwise be inexpressible, allowed her to slip seamlessly in and out of reality. In Basic Black with Pearls, it is magic realism that allows her to express her pain through Shirley’s consciousness. And it is magic realism that allows us to share that pain, felt as immediate and acute throughout the body of her work. It is her use of magic realism that will be the theme of a subsequent blog.

Rhoda Rabinowitz Green, author of Aspects of Nature (spring 2016)

Visit Rhoda’s page and book page on Facebook

Visit Rhoda’s author page and book page on Goodreads

more on Basic Black with Pearls by Helen Weinzweig here