With grace and courage Ann Elizabeth Carson looks to the past from the perspective of a contemporary feminist. A lively evocation of her aunts and their home in Cheltenham, Ontario reveals the rich and powerful ground for her own emerging sense of herself. As Toronto in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s comes to life in a rare blend of prose and poetry, Ann Elizabeth is caught unawares as the stories collectively uncover events that shaped her social-political outlook and reveal how our untold stories are inevitably woven into the fabric of our public lives. Laundry Lines: A Memoir in Stories and Poems is about the imperative to tell our stories for our survival, the complex emotional inheritance and painful undertow in families, the slow reconciliation with the blows and beauties meted out by life that comes with age, and the deep sensual salve offered by surrender to nature.

One unique feature of this book is Ann Elizabeth’s exploration of similarities between the unique coded language used by women and the one used by those working on the Underground Railway. The positioning of laundry on a line and particular quilted patterns were used to convey, for instance, whether a man/woman or a travel route was safe. Ann uses her skill as a long-time psychotherapist and writer to elucidate the role of women’s hidden language and how we communicate a rich subterranean world of emotion and knowledge subtly to one another.

“Ann Elizabeth Carson’s new collection, Laundry Lines, stories and poems, is as crisp as linens drying in the Manitoulin sunshine. A born storyteller Ann takes us on an extraordinary jaunt into history and poetry. She paints her experiences with an exquisite memory of places in Ontario from her youth to the present. By the end we have discovered more than her world, we have learned much about ourselves and who we will become. Ann’s writing is wise, compassionate and lyrical. Always in her work there is an enviable clarity and immeasurable strength.”

—Gianna Patriarca, story-teller and poet

“This is one of Canada’s voices, silenced for too long, that lived through the Robertson Davies era; the Morley Callaghan, Dorothy Livesay, Margaret Lawrence, Ethel Wilson and Anne Wilkinson years, now come to life in memoir and poetry. A rare combination of prose and poetry that returns to the experience of how women lived and were shaped by the 20th century. We do not have an array of widely published women poets prior to the 1960s. In Ann Elizabeth Carson’s Laundry Lines: Stories and Poems, we are able to witness how her language translates from one century to another into the new millennium.”

—Sonia Di Placido, poet, playwright, artist

“Looking back at the long laundry line of her life strung with memories Ann Elizabeth Carson’s book of poems and personal essays showcases stories strung juicy deep. Set in Cheltenham, Toronto and Manitoulin Island, Laundry Lines: Stories and Poems firmly rooted in the authors’ ‘mind cellar’ and focused on the moment, is visceral and sensuous, inviting a reader to open the ‘jewelled jars for every season preserved on mind shelves.’ This is the strong insistent voice of an elder who has some answers to offer and is not afraid to ask difficult questions.”

—Donna Langevin, poet, playright

“Ann Elizabeth Carson travels into her past to understand how her soul/person was shaped. She stumbles upon the various silences in her life: secrets and lies, stories of betrayal—even among trusted sisters—stories of loss and of enduring love. She breaks free from the wordless reticence that tied her and in a rare combination of visceral, sensuous prose and poetry, hangs out family secrets and cultural taboos to dry in Laundry Lines: A Memoir in Stories and Poems.”

—Jasmine D’Costa, author, Curry Is Thicker Than Water

We Must Tell Our Stories

We are born into a story. Layered threads woven deep

trail tracks on maps unread,

we gaze in wonder at what we are supposed to know.

We sleep through symbols, reluctant, yet challenged

to make them our own, grappling with what to keep,

or give away, as we meet our birthed-in story

always behind us, never forgotten. Earth-bound,

hidden or rearing up as needed, unforeseen,

while we gaze in wonder as what we are supposed to know

beckons — a hybrid flower opening to thick-fibred centuries,

threads of always has been, and a ready cache of seed

as we gaze in wonder at what we are supposed to know

about other stories yeasting; muffled murmurings

through time invite belief, disclose how differences leak

the story that gives us birth, may push us to speak

before the light goes out. Or else rejoin the motherlode

unknown. Listen. Hear the faint, waiting hums that heed

disembodied stories strung juicy deep, ours to be born into

when we gaze in wonder at the little we have come to know.

————————————————

Laundry Life

Monday morning is coffee smells and pulley squeaks

as my mother hangs clothes on two steel lines,

strung garden-length;

wooden pegs in a pouch on the line, the next peg

in her mouth — she could even talk around it.

First pinned are sheets and towels, then pants and skirts

pulled out to dangle over the tomato plants

at the back of the yard.

Shirts and blouses next, collars down

so shoulders dry without a mark. Underwear

(never bras!) hang close to the house, almost hidden

behind the vine-covered breakfast room wall.

Socks line up just so, toes point in one direction

(The days the heels and toes face each

other is a sure sign of trouble brewing.)

Rainy day lines criss-cross the open basement beams

over a hand-cranked mangle, steamy laundry tubs

and perspiring (not sweaty) mothers.

We kids peer in the neighbour’s window

to an identical scene, rest chins on the sill at driveway level,

yellow boots and knobby knees leave dry patches

on the pavement, along with the news from our side

kids were out in all weather

as long as they were together

Sheets hang blinding white in sunny winter rows,

dry stiff as boards, crack down the middle in a perfect

fold. My sister and I snicker

at the ossified pajama legs and other unseemly juttings.

We carry them under our arms into the house

to thaw over radiators.

The smell of frost and sunshine lingers

as they droop to the floor.

Waitressing to earn my university fees

between meals, I help the laundress string

long rows of flopping sheets

behind Monhegan’s Island Inn. Out of sight

of strolling guests the ropes stretch — salt would rust metal.

Long beach towels brush the grass,

their coloured curves, white fringed borders mirror

ocean waves that glint and foam along the shore.

I beg a corner of the line for uniforms, socks and “smalls”

hard to dry in my small dorm room.

Newly wed, our below-ground city apartment

boasts no green or cellar spaces. A tangle of ropes

stretched on a wooden frame in the bathtub

behind closed doors collapses without warning

under the weight of dripping hand-wrung garments.

Celebrating our eagerly awaited intimacy and freedom,

who cares? Until the baby came. I learned to drive

an old English mini, baby buckled in beside laundry

heaped high in the back seat.

I rattle up Spadina’s red cobbles to new machines

beside my mother’s basement laundry tubs.

Wash three loads, hang out, take in, hang out,

fold and fold and fold, catch up on family news,

neighbourhood gossip. Grandma and baby play,

cook a second-helping-of-meat dinner. Good trade.

A new baby on the way. We look

for a new home where children can play

And parents claim a toy-free corner. Find a hot little

down-payment-boosted house from parental pockets.

A big garden backs onto a stream (for now),

suburban women chat across fences, laundry placed

neat on “roundabouts.”

Plastic lines in four-square metal frames,

placed carefully for the wind to find drying room,

quiver with diapers, sleepers (two sizes now),

man shirts (collars down) in every straight-edged garden.

Back to the city (I said it was more children

a third is imminent) but no libraries or book stores,

no trees or art galleries, drove me crazy.

A creaky old house on a shady curved street. A washer

and dryer. No clothes shall hang below in the basement,

no roundabouts allowed in city gardens. We work

behind shiny painted doors. I never liked the neighbourhood.

No children peered in the windows.

The relief of Haliburton summers! Ropes strung on branches

between trees, sag under bathing suits, towels speckled with pollen,

insects fly into them, snagged unawares in the dappled sun.

We travel through two lakes and up the river to town

in the big dory once a week.

Sheets, machine-dried while we shop, are piled

beside bulging bags as four small chins drip ice cream

down their shirts. Lake smells

scent the beds for a night or two.

A marriage behind me with 22 years to sort:

what to keep, what else to leave behind? Move on

to a small detached, a friendly front verandah,

with two steel lines strung garden length from porch

to fence

by John, the youngest one,

the other children on their own. I dream

new gardens, hang a weekly laundry

with plastic pegs from the pouch on the line,

talk around the one in my mouth as new neighbours

air the week’s news.

Children grown — a stacked town-house,

a stacked washer/dryer in a cupboard,

the shower rod my laundry line for “hang to dry.”

Socks droop over water heater pipes,

sweaters on a towel drape over the toilet seat,

or lie flat in the bathtub.

On a good day

clothes dangle over chairs and plastic-covered metal rods,

the old wood drying rack re-incarnated, out of sight

behind the gate and the climbing hydrangea

in my patio haven. Until

John’s spring-time death. Scoured to the marrow, stripped

root and branch, flesh folds carefully over fragile bone.

No gardens.

No life-line

anywhere spreads everywhere endlessly ahead.

I take refuge

in the land and lakes of The Manitoulin,

stretch out on grass, rock or dock. Floating on the water

suspended between earth and sky, I watch a contrail

cleave the entrails of gunpowder clouds.

What origin propels? What path re-orients a destination?

When the light has changed colour, the horizon

disappeared and the world is unrecognizable.

I write to hear my heart, to feel my breath

salvage body and mind

unearth roots

redeem passion

1 review for Laundry Lines: Stories and Poems

| Format | Printed Copy, ePUB, PDF |

|---|

inannaadmin –

Laundry Lines

A Memoir in Stories and Poems

reviewed by Trudy Metcalf

Herizon Magazine – Winter 2016

http://herizons.ca/

Which parts of your story do you remember? Which would you choose, or dare to reveal, “for all to see and examine”?

These questions interest Ann Elizabeth Carson, poet, author, artist and retired psychotherapist. Carson, a woman holding 86 years of life experience, offers an intimate collection of poems and prose piec es in her latest book, Laundry Lines.

Carson begins with her assertion that “we are born into story.” Thus, the story is never ours alone, but is part of a much longer, deeper line stretching both out and back, tying the storyteller to her ancestors and to her descendants.

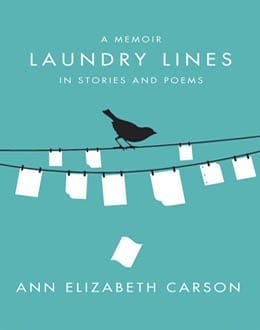

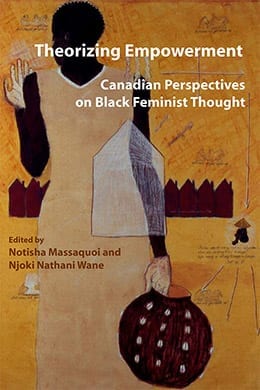

On the cover are Carson’s laundry lines, but no clothes are pegged, as one might expect. Instead, there hang rows of white paper, linen-crisp, blank, one in mid-fall. Readers need only come around to the other side, where they will find prose pieces about “the complex emotional inheritance and painful undertow in families,” coming of age during wartime, leatherback sea turtles and the death of a child. There are poems that delight, heal, warn or tell of Carson’s ardent attachment to the natural world, particularly in regard to her time spent on Ontario’s treasured Manitoulin Island.

This collection is an interesting mix, unflinching, heartening, wistful. Some of the pieces are more satisfying than others. I lost my way, for example, within the longest prose piece, “Weave and Mend,” unable at times to sort out the aunts and other relatives. At the same time, I gained an observer’s grasp of what being born into story means for Carson, of the sifting and sorting, the meaning-making that is the particular and complex work of people in later life. For Carson it is the “slow reconciliation with the blows and beauties meted out by life that comes with age.”

We need to pay attention to Ann Elizabeth Carson and to others like her who are committed to making sense of a long life being lived wholeheartedly . “I am a jumble of fascination and frustration,” she writes. How happy I am that it is so.

————

Book Review: A Memoir Laundry Lines in Stories and Poems

reviewed by Jim Pagiamtzis, Speaker and Author, 21 Connections Success Network – December 14, 2015

http://www.jimpagiamtzis.blogspot.ca/2015/12/with-grace-and-courage-ann-elizabeth.html

“A compelling book with stories and poems that will have you remembering how significant life we all live and the journey we are on is full of memories we cherish. The poems are the cherry on top to a enjoyable read ”

————

Laundry Lines: A Memoir in Stories and Poems

reviewed by Ellen B. Ryan

Writing Aging and Spirit – December 1, 2015

http://writingdownouryears.ca/writings-pegged-on-laundry-lines/

Monday morning is coffee smells and pulley squeaks

as my mother hangs clothes on two steel lines,

strung garden length;

wooden pegs in a pouch on the line, the next peg

in her mouth – she could even talk around it.

Profiled earlier in the Writing Aging and Spirit blog, Ann Elizabeth Carson finds herself at age 86 with much to say in poetry and prose about her life and the world within which she has lived. See Risks of Remembrance (2010) and We All Become Stories (2013).

Laundry Lines is a poetic exploration of women’s work in stories and poems. Laundry lines refers concretely to clothing pegged diligently by women and young girls onto outdoor lines in all types of weather. Carson also describes the line stretched across her Manitoulin cottage with ideas written on recipe cards conveniently set out for ongoing rearrangement –in the days before computer software for writing. [Take note of the cover image.] Behind the scenes runs the theme of quilted shapes set out with messages for slaves escaping to Ontario on the underground railroad or for loyalists dealing with invasion in 1812.

Women stitching, laughing, news-making, grieving

Together. Quilts track history. Quilts in cloth, wood or metal

Sign war routes, hidden foot-paths, ousted secrets, local beauty.

Proudly sold at church bazaars, high on a barn wall, or strung

Along a country highway. Anyone who looks can learn the stories.

Carson regales us with anecdotes about two maiden aunts who welcomed her to their weekend/summer place in a country town; coming of age during World War II; summers over the years at her cherished cottage on Manitoulin Island; and, more recently, ice storms in Toronto.

Four sisters, loving, faith-filled deeds and doing, well-socialized Protestant

introverts. … Their bleak, sorrowful sides were almost always as hidden as the

cellar floor …, sometimes schismed in a misjudged step when the light fails, and

as illuminated as [the] glittering jars in basement cold rooms, replenished yearly

by an interwoven web of independence, beauty, and practicality.

In fair weather, lake winds buffet jeans and T’s on a line

strung from tree to tree, flap child-memories

of a ‘good drying day’ as the last sock is hung.

Heels turn out, toes face each other on the days

when writing is stuck. …

The story Necessary Housekeeping swept me away. I was captured by the sweet tale of an immigrant cemetery gardener helping to maintain flowers at a grave, even as I was tugged more and more deeply by the information seeping through about the sad, unexpected loss the author had endured.

The interweaving of stories and poems works well to re-focus attention on nature, emotions, and narrative–all of which are featured in both forms. Marilyn Walsh’s striking ‘etchings with embroidery’ highlight the movement of thesethreads in Carson’s memoir.

————-

Laundry Lines: A Memoir in Stories and Poems

reviewed by Jon Muldoon

Beach Metro News – November 17, 2015

http://www.beachmetro.com/2015/11/17/beach-books-13/

Ann Elizabeth Carson’s latest book Laundry Lines: A Memoir in Stories and Poems paints pictures of small-town Ontario life and a Toronto that exists mainly in memories. These little portraits of distinct moments in time offer the chance for insight and lessons learned by reflecting on both the events and attitudes of the past, as she looks back on her formative years.

Focusing frequently on the influential women in her life, Carson delivers a mix of historical atmosphere, life lessons, and the sadness of occasional family conflict. She doesn’t shy away from that conflict either, mentioning her aunts’ role in cutting her mother out of a visit to their dying brother, or airing her grandparents’ separation in a time when preachers’ wives normally wouldn’t have even considered leaving their husband, no matter how mistreated they might have been.

It’s not all conflict and betrayals, however. Carson evokes a strong sense of nostalgia looking back at fond memories of childhood time spent in the company of her aunts Damaris and Gertrude at their rural home in Cheltenham, northwest of Toronto.

Likewise, rationing during the Second World War is noticed only in hindsight, and Carson recalls meals shared with soldiers in training from the military base down the street.

Carson’s memories also reach to more recent times – as recent as the December 2013 ice storm that shut down much of the East End, though the storm served to bring the author’s family closer together in a spot of power during widespread blackouts.

A summer home on Manitoulin Island also gets the poetic treatment, the rural setting of Carson’s warm-weather writing retreat inspiring an ode to the days before modern technology.

As with Carson’s previous book, We All Become Stories, Laundry Lines puts strong emphasis on memories. Her role as a collector of stories in that book shifts to that of expert storyteller here, and Laundry Lines hits the right mix of mood, atmosphere and personal history.

Laundry Lines—Telegraphing Memory and Experience

reviewed by Sean Arthur Joyce – October 5, 2015

https://chameleonfire1.wordpress.com/2015/10/05/laundry-lines-telegraphing-memory-and-experience/

Normally I wouldn’t have much interest in a collection so firmly based in women’s experience. It’s a history I can’t possibly hope to understand at the same level as a woman. But Laundry Lines by Ann Elizabeth Carson goes far beyond feminism. It’s an elder reaching through the past and connecting with the ingenuity any oppressed people will use to communicate in times of oppression. An elder looking for understanding, not blame. The previously little-known historical phenomenon of women on the Underground Railroad using laundry lines to convey messages is the central metaphor that underlies the prose and poetry of Laundry Lines. Much as the ‘hobos’ would do during the Great Depression years with a system of rocks on fenceposts, warning of unfriendly people or places one could get a meal for an odd job.

And what she seeks understanding for is the random chaos that can suddenly take a husband, a son, a sibling out of our lives. There is no melodrama here, merely the true-to-life daily round punctuated by moments of sudden, sharp clarity or awakening. Melodrama is not needed if one chooses to look wide and deep, to meditate on what life is trying to tell us and have the courage to actually learn. To refuse the challenge of introspection is to risk arrested development, to become frozen at a particular point in time—a caricature of oneself. Joseph Campbell would say such a person refused the call to adventure—a genuine tragedy of lost opportunities.

Carson’s poetry is light on metaphor but rich in sensual detail—she uses all her senses to pick out the scents, shapes and colours of a country market; to recall the bright rows of canning jars in her aunties’ basement during the Depression. Best of all, she eschews the cryptic language of postmodernism for straightforward, clear diction and the crisp image. It’s refreshing in a time when obfuscation in poetry is considered a sign of cleverness or innovation even as it alienates most readers. As women began looking optimistically at a better future, Carson’s own ruminations turn the stone over and over in her mind’s palm:

Her stage. Her act. Who writes

the play? Who composes the music?

Bone-bred, muscle molding,

stomach holding heritage.

—The Play

Summers spent on Manitoulin Island’s beautiful Lake Mindemoya provide some of the most exquisite moments in Carson’s poems. Here again she connects with the age-old tradition of writers and artists drawing from nature’s deep well. With so much poetry these days steeped in the urban environment in which the majority of our writers seem to live, this is a much-needed tonic, taking us straight to the source:

How many ways does the wind touch,

curl a sleeve, lift a collar, pucker

skin, disturb a strand of hair?

—Foreplay

In the best tradition of nature poetry, the poet becomes merely the vehicle, not the focus, for transmitting the essence of the scene:

Lily buds unfurl before

my eyes. The warming

sun spurs opening.

A fresh breeze stirs my hair,

nudge-rocks the canoe, shifts

the reeds to disturb a resting fish.

—Shore Reeds

In the best tradition of nature poetry, the poet becomes merely the vehicle, not the focus, for transmitting the essence of the scene:

Carson is a writer who chose to grapple with the call to adventure. Hers was a generation that made history. For the first time, women won the vote, were able to access the same level of education as men, and could become professionals in all fields, something unheard of before the 20th century. For Carson as for many women reading Steinem “changed my life.” She was clearly a strong woman already, facing down family crises with an inner steel. But with women’s increasing equality she could begin to see a career beyond family. Carson would work as a psychotherapist for 25 years. Nowadays we take all this for granted, forgetting how recently in history these things were not an option for women.

Carson’s spinster aunts were lucky to be friends with some revolutionary women. Charlotte Whitton, the slightly off-kilter first woman mayor of Ottawa, who campaigned to end the indentured child labour of British Home Children being shipped to Canada in the thousands. Marion Hilliard, “a prominent, ahead-of-her-time gynecologist at Women’s College Hospital, and author of A Woman Looks at Love and Life; Women and Fatigue.” And Eva Coon, another Toronto progressive who was Director of the YWCA. Carson got to eavesdrop on their conversations while the aunts crocheted over afternoon tea.

The details of the subject matter were beyond me at the time but conversations like this showed me that you can cook, clean, sew, quilt, garden, entertain and do all of these well, and also have a mind that shines at more than bridge, church meetings or the new book clubs.

Not for nothing does it seem like men and women speak different languages. With women’s laundry lines on the Underground Railroad as her subliminal track, Carson embeds the point. Yet her handling of reminiscences is something both men and women can relate to. As the beloved aunts Getty and Damaris fade into the half-light of their 80s, she is watching them slip away from her. The Waiting Room for Death that seems to be the tone of most seniors’ homes makes the stark contrast between Carson’s glowing girlhood memories of her aunts and the harrowing reality of aging:

We leave with little gifts of unmarked china, which means it’s old, or nineteenth century pressed glass she has tucked away in the one closet in her apartment, saved so that she will always “have something for us.” Sometimes I try to tell her how much she has given me down through the years. A nod, a little shrug, a deprecating smile and she changes the subject. Eventually I realize that the gifts are as complex as she is: beautiful, unique and practical, they are little “I love you’s,” small embodiments of her feelings and character. They also speak of her continuing need to make a contribution with something useful and beautiful. To be seen in a particular way, and with a reciprocity that means she is still part of family and community.

The melancholy is never cloying, never overwhelming. But present enough to underline the verité of her prose, that sense that pings with recognition in the reader. In the essay Memoirs—Sideways and Otherwise, I quote from Jane Austen, who recognizes memory as the most mysterious of human faculties. “It’s telling that one of the more tragic diseases that afflicts humans gradually erases memory,” I write there. “What’s left of a person when their memories are gone? It pains the heart to ask.” Or if not gone, distorted by time and stale emotion. But Carson has the courage not only to ask but to examine deeply.

As Carson writes so astutely, “…no narrative is impenetrable, and … the life stories we live with can be violently disrupted by feelings and memories that burst through without warning from the depths of one’s being.” An exercise in simple middle-class nostalgia this isn’t. “If I thought about their troubled family past I had assumed, given what I knew of how they lived,” she writes of her aunts, “that they had somehow come to terms with it in a way that enabled them to live contented and productive lives.” And of a shocking, unexpected act on the eve of an uncle’s death, she recalls: “Now the crater created by that explosion in me begins to fill with seeing, and understanding, how much less visible love is than strength. How, vulnerable to loss, love can twist into possessiveness and betrayal, hollowing our strength to a brittle skeleton. And survive that awful winter to grow new gardens.”

From the vantage point of her 86th year, Carson comes to realize the power even in the most self-contradictory of memories. Not only are they our personal history, they connect us with all history. We never know when one will be triggered into sudden life again, with unpredictable consequences. “They stand alone and side / by side. / Jewelled jars for every season / preserved on mind-shelves, waiting.” (Mind Cellar) But for all that, memories are embedded in us like DNA. Turning them over to taste their often bittersweet tang is as human as walking.

What origin propels? What path reorients a destination?

When the light has changed colour, the horizon

disappears and the world is unrecognizable.

I write to hear my heart, to feel my breath

salvage body and mind

unearth roots

redeem passion

—Laundry Life